War

Look back at our struggle for freedom,

Trace our present day's strength to its source;

And you'll find that man's pathway to glory

Is strewn with the bones of a horse.

~ Anonymous

The above pictures are of the battle of

Hastings as shown in the Bayeux Tapestry and of the battle of Waterloo. By

1066, the Normans had developed a highly skilled cavalry, and the English

foot-soldiers were no match for it.

For more information about the people and

horses on this page, see Profiles.

There

has been some question as to whether man drove the horse before he learned to

ride it. The argument that early horses were too small to be ridden seems

false; excavated skeletons indicate that early horses were the equal in size of

today's Arabian,

which though not large is capable of carrying a heavy rider without tiring.

It is certain however that the horse in harness had a far

greater impact on the progress of civilization than the horse with rider.

Agriculture, commerce, and conquest all depended on horse-drawn vehicles.

And of these, it was the war chariot--more than the merchant's cart--that

helped spread early civilizations.

Ancient warfare depended on mobility, and this the horse

provided. Horses were used with special effectiveness by the Hittites, an

aggressive Persian

people whose conquests made them the ruling power in Western

Asia around 1400 B.C. Historians of the horse have credited the early

Hittites with developing the Arabian

breed. Certainly they were

very sophisticated horsemen, yet it seems that they may have learned much about

the arts of horsemanship from the Mitanni, a group situated to the southeast of

them. Detailed instructions for the care and training of horses were

handed down on tablets by a Mitanni named Kikkuli, in service to Hittite

rulers. These instructions are astonishing in their knowledge and

exactness--about the distance and speed of daily exercise, the manner of

cooling out and rubdown, the kind and amount of fodder, etc. Such

expertise could have come only from centuries of work with horses, and this may

have to be credited to some earlier culture than that of the Hittites, possibly

that of the Mittani.

Hittite charioteers made excellent use of the flat, open

terrain of the North African and Near Eastern deserts. Their assaults were

made at overpowering speed by three-man chariots rolling on light, six-spoke

wheels. (Awesome speed and mobility was advantage of Hittites' light

three-man war chariots.)

The Greeks fought their wars in landscape too varied and

mountainous for effective use of chariots, so they developed the horse as a

cavalry mount. Miltiades, Philip of Macedon, and Alexander the Great won

amazing victories largely through their skillful and imaginative use of cavalry.

The Romans also conquered on horseback after learning from

their brilliant Carthaginian enemy, Hannibal, the value of a superbly trained

cavalry mounted on fast and durable desert horses.

Warfare in the Middle Ages was carried on by nobles riding

heavy horses. Never has the art of combat been more idealized, nor the war

horse more glorified. ("Great horse" of medieval warfare was

bred to huge size and heavily caparisoned for use in tournaments and

combat.) After modern weaponry made the Great Horse obsolete, it was

retired to peaceful service on the roads and farms of Europe and Britain.

____________________________________________________________________________________

The first English war horses were of stunted pony size and

merely conveyed the warriors to battle by chariot. As better horses were

bred they and the chariots became weapons of war, fighting equipment well

demonstrated by the Celtic Queen Boadicea.

The "knights of old" were small men, and it is unlikely that

their courses were very big horses. The Saracens rode rings around the

Crusaders, who soon acquired the same type of speedy, maneuverable horse.

Mass cavalry was not employed in Europe until the 17th century.

Although

those famed battle horses could carry a knight in armor, weighing about 450

pounds, their own battle armor will not fit the smallest modern Shire, and

judging by the portrayed position of riders' legs, they were not, in fact, the

giant horses we imagine.

Thousands of horses have been involved, and killed, in every

war and campaign up to World War II. In World War I there were appalling

losses among artillery, draft and pack horses. Although tanks and trench

warfare gave no opportunity for any large mounted attack, there were many

instances of the cavalry's proverbial courage and dash.

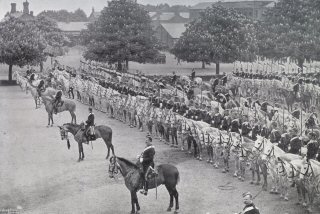

Today military horses are confined to the more peaceful

pastimes of the parade ground.

____________________________________________________________________________________

It is

truly said that empires have been built on the horse's back. Without the

strength, speed and willingness of the horse to do man's bidding, all-conquering

civilizations from the earliest days of the horse's domestication right up to

the 20th century could not have conquered other peoples and spread their

cultures throughout the world.

In the early days horses were used in battle mainly to pull

chariots, but gradually the use of cavalry developed. The Persians who

were expanding their empire around 500 BC, used cavalry to great effect.

Much of the success of the Islamic empire as it spread across

most of Europe was due to its fast and highly disciplined cavalry. The

European war-horse of this time, in contrast, was heavy and slow, as it had to

carry up to 500 lb (225 kg) of arms and protective armor, as well as its rider,

into battle.

With the invention of firearms, heavy armor became obsolete,

and new types of cavalry developed. These fell into three groups.

The dragoons were mounted on heavy, cob types; the lancers were mounted on

lighter horses, and were used for sudden assaults and fast flanking movements;

and the Hussars, also used for sudden attacks, were also mounted on light, fast

horses.

During the 19th century, with the development of shrapnel and

automatic weapons, the value of the cavalry charge gradually declined, although

horses were still used for artillery and troop movements, and very large numbers

of horses were used in all campaigns until after World War I.

In World War I, well-loved family horses, children's ponies

and commercial horses were commandeered into the army by force, never to be

returned to their families or owners. To put down a horse rather than

allow it to be taken was regarded as treason. In modern times horses are

used by armies all over the world for ceremonial purposes.

____________________________________________________________________________________

In the

Middle Ages, armor reached its zenith as horse and rider were clad in more and

more concealing plates of intricately jointed metal, which, of course, became

increasingly heavy. Knights often had to be hoisted onto their horses.

Horses' face-plates often had spikes on the forehead, giving

the horse the appearance of a metal unicorn. The body armor covered the

whole horse down to its elbows and stifles, protruding at the front to allow for

foreleg and knee movement. Neck armor was also made from jointed plates of

metal to allow for movement.

Horse armor continued to be used until the end of the

16th-century by which time the increasing use of firearms and cannon had

rendered it obsolete.

The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854 was one of the most disastrous cavalry charges ever. Out of 673 horses that charged the Russian artillery, only 260 survived. The development of automatic weapons and shrapnel during the 19th century gradually made massed cavalry charges of this sort obsolete.

During World War I, millions of horses were used on all parts of the front, and losses were appalling. The Scots Greys arrived at the Belgian frontier soon after the outbreak of war, and the famous grey horses had to be stained chestnut in order to camouflage them and prevent the enemy identifying their formation. The painting is a centre detail of Scotland Forever by Lady Butler, showing the charge of the greys at Waterloo.