Harness Racing

Trotting races, evolved from single "matches" between gentlemen out to prove their horse's superiority on the road, were first popularized in England, reaching a peak in the late 19th century. Legislation and undesirable practices then killed the sport in the United Kingdom, and it is only now struggling to stage a revival. But if trotting disappeared as a recognized sport from the British scene, the enormous success of harness racing in the United States is due, in part, to the blood of imported British trotting stallions in the past. In Europe, as well as in many other countries, this form of racing has a top priority in sport.

For the

first few decades of the 19th century harness racing was fairly informal, a

matter of owners challenging each other on some suitable stretch of road.

If trotters were raced on tracks, it was usually under saddle. Trotting

was spared the religious disapproval which closed the flat-racing tracks of the

Northeast in 1802. Lawmakers reasoned that since a horse in a trotting

race was not running as fast as it could run--in a faster gait--trotting

races weren't really races and therefore were not immoral. Thus favored,

the sport flourished and, by the 1840's, improved tracks and sulkies made racing

in harness the preferred style for trotters. Harness racing gained in

popularity up to the Civil War, but when it was resumed after the war its

disorganization and crooked practices were a disgrace to the sporting

scene. Through the 1860's strenuous reforms were undertaken and by 1870 a

governing body had been set up that in time became the National Trotting

Association. Harness racing finished out the century in a very healthy

condition, honestly conducted and attracting an increasing number of breeders,

owners, and fans.

Two inventions gave impetus to the sport in the late-century

years. First, in 1885, the hopple was introduced to the pacing game.

Though faster generally than trotters, pacers were less popular with bettors

because of their tendency to break out of the pacing stride. (The trotter

that breaks stride can be urged back into it; the pacer cannot.) The

hopple was simply a harness that prevented the horse from running in any gait

but the pace. Next, in 1895, came the light, "bike"-type sulky

with pneumatic tires and ball-bearing wheels. Pulling this vehicle, horses

began shaving seconds from the records. In 1897 the two-minute mile, once

thought impossible, was cracked by the pacer Star Pointer in a time of

1:59&1/4 (1 minute, 59 and 1/4 seconds).

At the turn of the century the legendary pacer Dan Patch

began a career that made him almost a national hero. He raced for nine

years and 30 times ran the mile in under two minutes. At age nine he did

it in 1:54&1/4, a pacing record that stood for 33 years.

Harness racing declined in the Twenties and Thirties, though

the sport was kept alive at smaller tracks and fairgrounds. The Standardbreds

were due for a stunning comeback, however, and it began on an

evening in September, 1940, at Roosevelt Raceway on Long Island when night-time

harness racing made its debut.

Harness racing entered an era of fabulous popularity in the

mid-Forties. Night racing attracted afternoon flat-track fans and people

with daytime jobs. And the type of racing they saw was more exciting than

before. False starts were eliminated by the automobile-mounted starting

gate, introduced in 1946. The old custom of deciding a winner on the best

of several heats was largely abandoned in favor of single-heat decisions.

As attendance climbed, track managements enlarged and expanded their plants.

It is still a golden era for the Standardbreds. About

25 million people attend trotting and pacing races annually, spending nearly $2

billion at the betting windows. In the vintage year of 1969 Nevele Pride

earned the title "fastest trotter in history" with a mile in

1:54&4/5, and New Zealand-bred pacer Cardigan Bay retired at age 12 as the

first Standardbred

to earn a million dollars.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Inside Harness Racing

Harness racing--a sport as American as baseball-has a distinctly democratic

flavor. The more aristocratic patrons of horse sports have traditionally

favored Thoroughbred

racing (or flat

racing), "the sport of kings." Special to

the harness scene is the close involvement of owners with the day-to-day careers

of their horses. It costs much less to own and race a Standardbred

than a Thoroughbred, and the harness horse has more years of track life to reward its

owner's investment. Many owners are in the sport of harness racing with

just one horse, while in Thoroughbred racing it is more usual for owners to

command whole stables of promising runners. Also, it is not unusual for Standardbred

owners to drive their horses on the track--in workouts and

sometimes in races. The Standardbred

has a calm disposition, and the

dangers of driving one do not approach those of piloting a Thoroughbred.

Few sports performers have longer careers than sulky

drivers. With luck, a man can start in his teens and retire in his

seventies. Some drivers train the animals they race; many of the leading

drivers are also owners and breeders. The dream success story of harness

racing is that of Mr. Harrison Hoyt, a Connecticut businessman and amateur

driver, who won the 1948 Hambletonian--the most prestigious race of the harness

world--driving Demon Hanover, a horse he had bought as a yearling and trained

himself.

The breeding of trotters and pacers is on a much smaller

scale than that of Thoroughbreds. There are two major establishments,

several farms of important size, and a number of medium-size to small

operations.

____________________________________________________________________________________

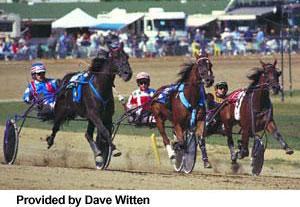

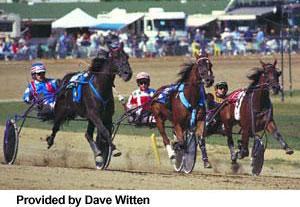

A Harness Race

Harness

tracks are usually a half-mile or five-eighths of a mile long. A few are

mile long ovals. Surfaces are firm, in contrast to the soft tracks of flat

racing.

To begin a race, horses are guided into their positions side

by side along the automobile-mounted starting gate. To effect a running

start, the car moves down the track at a gradually increasing rate of speed,

sulkies moving in line behind it. As the starting post is reached, the car

speeds ahead and to one side. The wing-like gates fold away to clear the

field.

The race is likely to be for the mile distance, although odd

distances up to two miles are sometimes run. The driver should be a master

tactician, keeping every move of his horse in tight control. On the longer

oval of a mile track, he may attempt a pass on the turn, and he takes advantage

of the longer straightaways. If he has been lucky enough to draw a place

near the rail in the pre-race draw for starting position, he should be able to

pull well ahead in the field at the outset of the race, when all runners move in

toward the rail.

As one post after another is passed, the driver waits for the

right moment to make his move for the lead. If he has been clever, he

won't find his four-foot-wide sulky boxed in when the time comes, for if he cuts

in, crowds, or collides with another sulky he will be penalized. He should

know just how much he can ask of his horse. Two bursts of top speed are

about all the average horse can deliver. The wise driver knows just when

to "use" his horse. If the animal performs and finishes first,

it takes only a few minutes for the judges and film replay to confirm that he

has won a fairly run race.