Training

(the Horse and the Rider)

"The

one great precept and practice in using a horse is this, never deal with him

when you are in a fit of passion."

—Xenophon,

The Art Of Horsemanship, 400 BC

I probably will not use sketches and such of how to ride at this point. I once read a book that does not show "a 'correct seat' because too much harm can result from over-emphasizing an ideal in purely graphic depiction." I quite agree; however, I don't know what I may decide to do in the future.

It takes seven years to train a Lipizzaner to perfection in only one or two airs, and twelve years are considered necessary to train a man before he reaches the height of his art and his ability to ride a perfectly schooled Lipizzaner. It may take twenty years before one is regarded as an efficient and competent judge of in-hand young stock, hunter riding classes, dressage or coaching teams. Similarly, you may require thirty years of painstaking study in several languages before you have learnt enough to pass on information by means of lectures or the written word.

____________________________________________________________________________________

The horse is

useful to man because of its tendency to move forward when urged to do so--its

"excitability to motion." Equally important, the horse can be educated to

respond in highly controlled ways to the urgings of its rider or driver.

As directed, it will move fast or slow, turn this way or that, step in different

gaits, jump over obstacles, etc. The primary means of controlling a horse

is a bit which is placed crosswise in the horse's mouth and to which reins are

attached. A rider or driver manipulates the reins so as to exert pressures

on the bit and the horse responds to these pressures as it has been trained to

do. A rider also uses his body to control the horse, through leg pressures

and shifts of weight. The modern horse, then, is foremost an animal to be

ridden (or driven). This aptitude, simply expressed in Latin, provided its

scientific name, Equus caballus.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Intelligence (of the Horse)

The question of

intelligence applies no less to the horse than to any other animal. How

much, if anything, it "knows" remains a matter for scientific

investigation. It is certain, however, that the sensory system of the

horse supplies it with much information. Its sight is extremely keen, with

such a wide angle of vision that it can see almost straight behind.

Extraordinary, too, are its hearing and smell, its reflexes and motor

coordination. In addition, the horse has remarkable memory powers.

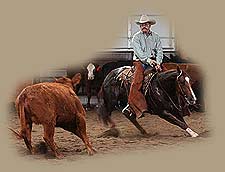

Like the famous Lipizzan

stallions of the Spanish Riding

School of Vienna, it can be trained to perform involved routines. Like the

cutting horse of the Western range, it can learn to anticipate and out-maneuver

the dodgings of a runaway steer. Its excellent memory can be a liability,

too, for any reminder of a bad scare can cause a horse to react violently.

By nature, the horse is timid. A vicious horse is

either a quirk of nature or the product of mishandling. The stallion's

tendency to aggressive, even hostile, behavior proceeds from his nature and

function as a sire, and is not a cause of concern to experienced horsemen.

Some types of horses, it is true, are less good-natured than others and require

a firmer hand in training and handling.

Thus, the personality of any individual horse is an amalgam

of several influences: his breed characteristics, the treatment he

receives, and his individual make-up. A horse may be high-strung or

nonchalant, "giving" or laggard, quick or slow to learn. He has

enough intelligence to be useful to man in many different ways, but not enough

to realize that he has the advantage in physical strength.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Riding

A horse has to be

carefully prepared before it is ready to be ridden. This is known as

"breaking" and "schooling." The horse has to get used

to having a rider on its back, and must learn to obey commands. A horse

can be broken for riding when it is three years old, and will have an active

life until it is 20, if well cared for. (Horses normally live for 25 to 30

years.)

A rider has just as much to learn as a horse does. He

must learn to sit so that the horse is well-balanced and can move freely.

He must also learn to give the horse signals it can understand.

If you want to learn to ride, find a riding school that is

approved, so you can be sure your teacher is a good one. You should be

given a quiet, well-schooled horse or pony to begin on.

These are the aids a rider uses to

control his horse:

Hands: These hold the reins which control the bit. The

bit lies on a sensitive part of the horse's jaw, so you must keep a steady but

gentle contact with the bit. Use your hands to slow your horse down, and

to turn it to the right or left.

Legs: Use your lower leg and heel to make your horse move

forward, and turn properly (bending its spine). Your legs should be close

to the horse's body. Your heels should be pushed down. If the horse

moves suddenly, try to keep your body relaxed.

Body: Body weight can be used to drive the horse

forward. If you want to slow down, let your weight sink into the

saddle. The horse will easily keep its balance if your seat is

proper. The legs and reins are all that is needed to make the horse change

direction.

Voice: Horses have very sharp hearing, and can learn to

recognize many sounds. To encourage your horse to move forward if it

hesitates, click your tongue. A slow, quiet "Whoa," used

with the proper seat and rein movement, will slow it down. Never scream or

shout near a horse. This will frighten it and it may bolt.

____________________________________________________________________________________

A rider is not necessarily

a horseman. He may be adequate at the different paces, remain

"put" over

moderate fences and be capable of making quiet horses comply with his

wishes. But if he is not "at one" with his mount, both physically and

mentally, if he does not share that indescribable partnership, possible between

man and horse, and never feels the mutual confidence that enables them to

"rise

to the occasion" together, then he is not a horseman. It takes time, and

intuition, but to be a good horseman is to enjoy the ultimate heights of riding.

There are many different methods of riding, each evolved for

a different purpose. The jockey, with very short leathers, seat far

forward and clear of the saddle, is attuned to the speed of the race

horse. The show-jumper sits deep in order to thrust his horse toward a

fence with his seat-bones, and then takes the weight off its loins when

airborne. The cowboy's legs are nearly straight, his seat maintained

almost entirely by balance--riding "Western" being the most comfortable

position for long hours in the saddle. The Australian Aborigine is a

superb stockman and usually rides bareback. The Englishman "out

riding"

sits easily, his leathers of a length that is the most comfortable. All

these are different examples of the same thing, each rider sharing the

lightness, rhythm, balance and understanding that makes them horsemen in harmony

with their horses.

The best method of learning to ride is to attend a reputable

riding school, where the standard of teaching and condition of the horses is

known to be good. Saving a few dollars by going to one of the less

reliable schools may result in incorrect or negligible instruction.

Good riding is an art, appearing, to the uninitiated, to

obtain the horse's willing cooperation with the minimum effort. Rider and

horse must be balanced, the horse's weight distributed beneath you, his head

correctly bent to "accept" the bit. Reins are long enough to give a light

contact with his mouth, but short enough for control. Use seat and legs to

keep him up to the bit. Slight pressure with right rein and left leg will

turn him to the right, with opposite aids for turning left. On circles,

use the outside leg further back to prevent the horse's hindquarters from

swinging out.

The good rider is both relaxed and still. He should sit

deep, but light, in the saddle, with thighs and calves providing the grip.

Ankles should be unstiffened, feet facing more or less forward, toes up.

The lower leg increases speed by slight pressure, but otherwise lies close to

the horse's side, without touching. Constant kicking makes the horse

unresponsive. Your seat is "balanced" when you are independent of any

support by the reins and of your horse's movement.

Reins are a means of communication and indication through

your horse's sensitive mouth (hard mouths come with poor riding). Hands

and wrists should be sympathetic, thumbs uppermost and pointing forward, the

fingers "giving" to the horse's mouth like a sponge being squeezed of

water. Do not yank your horse to a halt, but keep your hands still with an

even pressure on the reins, then push him forward onto his bit with your

legs. The schooled horse meets an unyielding surface, "gives," and

slows. Think of him as a tube of toothpaste, your legs supplying the

energy--the paste. You "push him onto his bit" and apply the cap to the

tube--his energy is bottled up between your legs and your hands.

Horses love being talked to, but hate being shouted at.

Your voice is an important "aid," but only raise it when really necessary.

Your horse will learn to "come to call" in the field, and recognize your voice

near the stable with a whinny.

You should learn the rudiments of jumping--walking and

trotting over very low poles--as you learn to ride. This way the idea of

jumping loses any aspect of fear and becomes a natural ingredient of the art of

riding.

Finally, remember that a young horse's natural reaction is to

swerve away from objects that, to him, appear dangerous. Patience and

schooling minimize this tendency, but the good rider is always aware of

it. If your horse indicates shying, use of the rein furthest from the

feared object, backed up with pressure of both legs, helps to keep him

straight. Your voice will reassure and calm him.

There are various

"seats"

in riding, but the General Purpose Seat is the most useful for the ordinary

rider. After mastering walking and trotting, the next step is the

canter. The rider's seat barely comes away from the saddle, and looking

down or leaning forward are incorrect. There must be nothing stiff about

the position, with a supple waist, and shoulders and head "giving" to the rhythm

of the canter. With each increase in pace, the reins are shortened

slightly to maintain contact.

Galloping is a pace of four-time, the horse's fastest speed, and should not be

attempted by beginners until they have achieved an independent sea, and then

only with an obedient horse. At this pace the rider's weight is adjusted

forward, and from just above to just below the knee. The seat comes

slightly out of the saddle, the body inclining forward in balance with the

horse.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Training the Race horse

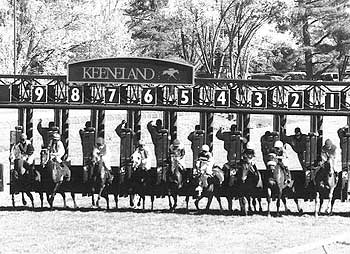

Training a horse for

"the sport of kings" is a long and painstaking process. When

only a few days old, the foal is fitted with a simple halter and taught the

touch of the human hand. Months later, as a colt, he is bridled and put

through some beginner's paces at the end of a 30-foot line called the longe

(pronounced "lunge"). Jogging in circles around his trainer, he

learns to move well in the various gaits and to respond to commands. When

big enough to carry a man, he is saddled for the first time and taught to walk

with rider. As training progresses, he learns to run and to overcome his

timidity while maintaining proper track deportment. By age two, he has

started rehearsals for real racing, working out at gradually more demanding

paces and being schooled for the starting gate. Very soon he is ready for

his "maiden" race.

The Thoroughbred

breeding industry produces some 15,000

Thoroughbreds annually. Many horsemen are concerned that out of this crop

the only horse capable of winning the Triple Crown since Citation in 1948 has

been the superbly made Secretariat, winner in 1973. (This article is from

a 1974 publication.) The economics of breeding have made it necessary for

owners to start their horses racing as early as possible to regain the many

thousands of dollars spent on purchase price (or sire's stud fee), training,

keep, and registration fees. It may be that performance pressures are

preventing the young Thoroughbreds from maturing properly and realizing their

potential. However, with the breed in the hands of highly devoted

horsemen, its continuing greatness seems assured.

A man

needs someone to believe in him. A horse has this big need, too.

Whether he is bred to race or show-jump or draw a plow, he needs someone who

believes in his power to run or jump or pull.

Outward signs of the special qualities of the Thoroughbred

may not be visible in

colthood. Sometimes the colt is a playboy who resents having to grow

up. He skitters around his pasture, full of wild notions, and when he is

put into training he either throws a tantrum or bobbles along the track from

side to side as if he were catching butterflies.

It is then a colt needs championing, needs someone who senses

strong fiber and spirit underneath the giddiness. This friend is not

always the trainer or owner; sometimes it is the man who rubs, feeds, and waters

him--his groom. How that groom tries to get his thoughts through to owner

and to trainer! Persistently he corners them and so dead earnest is his

talk that the men laugh at the big sounding words and then walk off, pondering

the seeds in them. So the colt gets another chance, and another.

Then one day he pushes against the wind and opens his nostrils to suck it

in. Suddenly he wants to run and he does, and he wins! And

there at his side, ready with soft warm blanket, ready with words of praise,

ready with rub cloths, stands his groom, feeling big in the chest and good.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Training the Standardbred

Training begins with the

first touch of a man's hand, soon after the foal is dropped by its dam. A

halter is placed on its head which it wears during the first months of

life. Only as a yearling is it introduced to the pieces of the harness,

first the bride, then one by one the other straps and fastenings of the

complicated rig. Next the young horse is taught to walk ahead of his

trainer, guided by very long reins. After a week or two of learning to

turn right or left in response to the reins, he is hitched to a cart and jogged,

gently and slowly in early sessions, faster as he adapts. He will be

fitted with several combinations of shoes until his trainer is satisfied that

the perfect combination of shoes and toe weights has been hit upon--one that

will promote an extended stride with perfect balance. A trotter's shoes

weigh eight ounces or so, a pacer's about five.

In his early jogs, the horse develops his gait, gradually

working up to faster times. If he seems ready for the track, the driver

begins to extend him in four-mile jogs climaxed with a brief all-out burst of

speed. As his times get faster, the workouts are reduced to two a

week. By the day of his first real race he will have logged about 700

miles.

Each day at a harness track is a lesson in how to win

races. It begins at sun-up, when the trainer arrives to check his

horses. With assistant and stable hands, the day is planned out.

They spend the morning working out the horses and the afternoon in such jobs as

shoeing their runners and sizing up the competition.

If post-time for the first race is 8:30 P.M., the horses in

the first race are on the track at 6:30 to begin the warm-up process.

Three times is these two hours each horse will be jogged, then returned to the

paddock for sponging and cooling out. First jog is in light harness and

covers five miles, half of that distance at speed. Again, after a

half-hour interval, the horse returns and makes some practice starts, finishing

off with a mile run at a good clip. In his last appearance before the

race, the horse runs another mile at a little less than all-out speed.

This is about 40 minutes before his race. (Between races, the track is

constantly in use by horses making their practice runs.)

In this elaborate warm-up procedure, the horse is worked for

several miles even before he is called upon to give his all. Strenuous as

it seems, the trotter or pacer needs this loosening in order to run in top

form. He is still limbering up in the last moments before being summoned

to the starting gate.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Do Horses Think?

Horses certainly do think

-- to survive in the wild they have had to develop the ability to think

extremely quickly (although their initial "startle" reflex on becoming

aware of dangers such as a predator is more instinct than thinking). Once

they have become aware of a potential danger, they must quickly assess the

situation, and decide whether or not to run away, or just move to keep the

danger outside their personal space.

Some horses seem to show more intelligent thought than

others. For example, some work out quite quickly how to undo their stable

bolts and escape -- a few even learn how to undo the doors of other horses in

the barn and let out the occupants. This requires both planning and

understanding of the outcome of their action.

The ability to look ahead shows high-level thinking ability,

and although horses may not be able to plan and look ahead to the extent that

humans can, they understand time and know that certain things will happen at a

certain time of day, for example feed times. If a horse is thirsty, it has

to think to go to the water source. If it is in a field at feed time, it

shows thinking ability by wandering over to the gate and looking expectantly

(looking ahead) in the direction from which you will come with its feed bucket.

In order, for example, to complete a round of jumps, the

horse has to concentrate quite hard, thinking about the various aids its rider

is giving it and what they mean -- more impulsion, slow down, turn here -- and

it has to realize that the jump its rider has aimed it at is the one it is

required to clear. It then has to gauge its own strides, or perhaps

regulate them in accordance with its rider's instructions, and take off into the

air in the right place. Only the horse itself can decide, by thinking

quickly, just how high to propel itself into the air. This takes

considerable judgement, even with experience and practice, and cannot be done

without clear thought.

Reasoning Power

It is often said that

horses have no reasoning power, reasoning being the ability to think out a

problem or situation and overcome it. Many experienced and sensitive

horsepeople deny this, knowing from their own experience that horses can

solve problems. In one informal experiment, horses were given feeds in

buckets with loose lids which they had to remove before they could eat.

Most of the horses clearly considered the situation and by various means removed

the lids calmly. Only a few bashed frustratedly at the buckets, showing no

ability to think through the problem.

In another incident, a mare was caught by one hind leg in a

loose wire fence. She was seen to turn her head and look for several

seconds at the loop of wire round her leg. She then raised her other hind

leg, felt the wire carefully with her (shod) hoof, stepped on the loop pressing

it down to the ground and freed her trapped leg. This is an obvious

example of clear thought and reasoning power.

Mares and foals in domesticity are usually weaned earlier than would happen in the wild. If they are reunited, they will recognize each other.

Horses that work with cattle have to be very quick thinking to anticipate the direction the steer or calf will take, and to react instantly.

A stallion rears up to intimidate a rival, often lashing out with its front feet. Horses also rear up in play.

Reacting to a Threat

A horse confronted by

something frightening or potentially dangerous will analyze the threat and

respond according to the perceived seriousness of the danger. Initially it

will show the "startle response" -- it will raise its head, prick up

its ears and point them forward, flare its nostrils to take in potentially

informative smells and open its eyes wide to see as much as possible. Its

body will be tense and its hind legs will come slightly more forward under the

body ready to take its weight if the danger is such that it decides to wheel

round and gallop off to safety.

If in the case, for example, of an intruder, the horse

decides to stand its ground, it will probably thrust its head forward

aggressively, with ears back, nostrils wrinkled up and back and maybe bare its

teeth and open the mouth as a warning of its intention to bite if the

threatening intruder does not retreat. Should the intruder not

retreat, it will threaten more aggressively, moving forward with the expression

described, maybe with head low and neck stretched out, lunging out at the

intruder with its teeth.

If, in the case of a horse intruder, the other horse does not

withdraw, a fight may ensue. Both horses will maintain an angry,

aggressive expression and they will bite at each other anywhere within

reach. Males, in particular, often rear up with flailing forelegs, trying

to come down on to the back of their opponent and get them down onto the ground

where they can be trampled and kicked. They also back into each other,

kicking out rapidly in succession with both hind feet at once. Such

kicking is a more common method of fighting for mares.

____________________________________________________________________________________

How Horses Learn

Survival in the wild is

often dependent on an ability to adapt rapidly to new conditions. Horses

can learn fast if the right training is given.

Horses learn mainly by means of association of ideas.

It has been scientifically and practically proved that if a horse can be made to

associate a particular task, even an unpleasant or frightening one, with

something pleasant he will tolerate it much more readily. For instance, a

horse that does not like being shod will accept it in time if it learns that it

will be fed some favourite tidbits, or have a net of sweet hay to nibble at,

during the process. If you are trying to teach a horse to move over in the

stable, for example by pushing it so that it moves away, and at the same time

saying "over", it soon learns to associate the push with the action

and before long will move over to a slight pressure on its side or just the word

"over". The position of the handler's body is important

too. For example, if you stand directly in front of or behind it when

saying "over", it will not know which way to move.

Horses learn their daily routine quickly and watch the goings

on, listen to the various sounds, and absorb daily happenings. They

quickly associate the rattle of feed buckets with the appearance of feed, for

instance, and the sight of someone carrying their saddle and bridle with work or

going for a hack.

They are also quick to absorb atmosphere and can

differentiate between a pleased, praising or calming tone in the human voice and

a sharp, cross, reprimanding tone, or an urging, encouraging one.

At the

beginning of its training, the horse learns basic commands like "walk

on" and "whoa" on the lunge. Being led by a helper, the

horse is shown what the different sounds mean. Soon it learns the commands

well enough to work mainly from the voice alone.

Keep It Simple

Horses learn short, simple sounds best. Although a stream of words said in a particular tone can convey your feelings--such as calming down or urging on--when you want the horse to perform a particular movement it is best to use short sounds of up to three syllables. As horses recognize the actual sound, the tone and inflection of the voice is very important. Always give commands in the same way so as not to confuse the horse. When you buy a new horse, ask the previous owner to demonstrate the exact way in which he or she gave it commands so you can imitate them, even down to their accent if necessary. If the previous owner asked the horse to "trot on" and you use the long drawn-out command "terr-ot", you cannot blame the horse for not complying.

Racehorses are introduced to starting stalls as youngsters by being walked through them, then standing in them; they soon learn that the gates flying open means "gallop".

Circus horses, particularly those touring the same route every year, often have to learn new acts regularly, as their audiences will want to see something different each time. However, they never forget their old routines, and can usually be put through a movement after several years' break and perform it faultlessly. Even just the sound of a particular tune can set them off on an old routine.

To reach the high standards required at the Spanish Riding School, horses must learn movements that are progressively more difficult, both mentally and physically; they must show increasing understanding of their riders' requirements, and respond to finer and finer aids.

Reward versus Punishment

Horses are easily upset and startled, so it is best to use

reward training rather than punishment training. For instance, when a

horse does something right praise it consistently by always using the words

"good boy" said in the same tone. If it does something wrong,

however, it's best to give no response at all but make your aids clearer, then

praise it when it does get it right. Most horses do want to please.

There are times when a horse may be blatantly naughty or

dominating. In such cases, one sharp smack or crack of the whip

used at the same time as saying the word "no" crossly,

delivered the instant it does wrong, will convey the message that this behavior

is not wanted.

It is essential that both praise and punishment are

administered within one second of the horse's action, otherwise the horse

cannot connect your response with whatever it did and will learn nothing.

It must associate your action with its own, good or bad, in order to learn

whether you are pleased or not. This is the way its brain works and is

essential to the learning process.

Inadvertent Learning

If a horse comes to associate an action with something unpleasant it will not want to do it. For example, if a horse receives a painful jab in the mouth every time it jumps, it will quickly learn that jumping means pain and will start refusing; if it is kicked on the hip every time it is mounted it will soon start to become difficult to mount, having learned that the process is unpleasant.