Identify the Horse

"There's something about the outside of a horse that's

good for the inside of a man."

~ Sir Winston Churchill

I don't really

know where all the information I'm finding should go, so this is sort of a

general info page right now. It may eventually be devoted just to ways to

tell the different breeds apart. (It will probably, of course, include

ways to tell different kinds of equines apart--horse vs. donkey, etc. For

example, it doesn't really matter how big or small a horse-like animal is--if

its ears are disproportionately long, like more than half the length of its

face--it's probably at least part donkey!) If you have any suggestions for

this page, please contact me.

____________________________________________________________________________________

How?

At first, it is difficult to tell what breed a horse or pony is, but after a while, it becomes easier. Here are some clues to help you:

If the horse carries its tail high and has a dished profile (a face that curves in), it probably has some Arab blood, such as an Anglo-Arab or a Welsh pony.

If it is small and sturdy, with a long, rough coat, it is probably a mountain or moorland pony, like a Highland or Dartmoor pony.

If the horse is tall, with long legs, a fine skin and coat, and a light build, it might be a Thoroughbred.

If it is big, heavy and slow, with feather (long hairs) around its fetlocks, it is probably a draft horse, like a Percheron or a Shire.

One should not confuse the terms purebred and Thoroughbred. Only about 8 of every 100 horses in the United States are purebred. Thoroughbred refers only to English race horses.

Where?

Many of the horses you see are likely to be cross-bred. It can be fun trying to guess which different breeds their ancestors were. Look for pure-bred horses and ponies at:

Horse shows, where there are classes for various breeds.

Stud farms, where horses are bred. (This is probably the best place to find pure breeds.)

The breed's natural surroundings such as the marshes on Assateague Island (for the Assateague/Chincoteague pony).

Racing stables or racetracks (these are the best places to see Thoroughbreds).

Riding stables. At the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, for example, you will see Lipizzaners.

Ask at your nearest riding school if any of their horses or ponies are pure-bred.

Sometimes color can be a clue. Most

breeds are the common colors - bay, brown, chestnut, and gray. However,

some are generally a particular color. For example, the Fjord

pony is usually dun.

You will be able to find some of

the breeds all over North America. Others live either in particular areas

of the country, or in other countries, so they will be harder to find.

Others are very rare indeed; you will probably see them only in zoos, or in a

film or on television.

____________________________________________________________________________________

General Information

The horse is one of the

most intelligent and versatile of animals, adapting itself readily to any

environment and having a memory good enough to find its own way back to its

stable, as well as quickly learning commands. A horse can vary in weight

from about 300 pounds (a small Shetland pony) to 2,400 pounds (a large draft)

and in height from about 3 feet to about 5 feet 8 inches.

The horse possesses

a keen sense of hearing, smell and sight. Its eyes, the largest of any

land animal, are located on the sides of the head and move independently of each

other. Its wide nostrils help it breathe easier when running or working.

The body of the horse is covered

with thick hair, grown every fall and shed every spring.

A healthy adult horse should have a pulse of

between 36 and 40 beats per minute while at rest.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Horses are the hoofed, herbivorous species that include the zebra, donkey, and mule. There are several groups of species of horses. One contains the zebra, which is native to Africa and another has the donkey, including the kiang and onager of Asia and the wild ass of Africa. The third group contains Przewalski's wild horse, which is now only able to be found only in captivity. The only extant true wild horse, it produces fertile offspring when crossed with the domestic horse. Other "wild" horses can be found, including the mustang. These horses have been seen living in the wild.

Modern Horses

One of the most noted characteristics of the horse is that it has only one toe, called the hoof. The hoof has a hard covering, made of keratin. There are several parts of the hoof. A horse's skull is very long, and horses have 44 teeth. A horse uses it's incisors, which form a semicircle, to crop grass and other plants. A horse's skull is composed of 34 bones. There is a gap in-between the horse's premolars and other teeth, which is where the bit is settled when the horse is being driven or ridden. All the teeth have long crowns and pretty short roots. A large horse's stomach can hold approximately 10 gallons at one time.

Male and female horses both are mature enough to reproduce by the age of two. However, they are rarely used for breeding until they are at least three years of age. The gestation period is about 11 months, and single births are the rule. Twins are a rarity, and only a few births of three or more foals have ever been recorded.

You can find more

information of this sort on Riding Techniques. (I took this section from

an email I received so I really don't know where it's from.)

____________________________________________________________________________________

Conformation

A sound and attractive horse of any breed is pleasing to the eye and shows quality in the "points of conformation." Below are some of the ideals that most light-horse breeds have in common.

Croup: sloping

or nearly horizontal, according to function of breed, but generally long and

muscular.

Legs: positioned for a square, solid stance. Forelegs, seen

from the front, are straight, with feet set about a hoof's breadth apart.

Hind legs, viewed from behind, are straight and perpendicular to the body.

Bones are flat, not rounded. Tendons large and well defined. No

puffiness in joints.

Pasterns: neither too long nor too short; angle of about 60 degrees

is ideal for shock-absorbing function.

Hoofs: rounded, with no cracks or rings.

Hindquarters: clean-cut and muscular.

Back: well blended with front and hindquarters and in good

proportion; short is ideal of most breeds.

Chest: broad and deep for good lung capacity.

Shoulders: sloping (i.e., line from withers to point of shoulder),

not straight or steep. Good angulation of shoulder and arm provides

springiness and resistance to shocks.

Neck: long in most fine breeds, well set into shoulders.

Eyes: prominent, wide-set, expressive of good disposition.

Head: proportioned for balance, i.e., large on a short neck, small

on a long neck. Bone structure well defined. Forehead broad and

flat, and profile straight or slightly dished. (A Roman nose is

characteristic of draft breeds.)

Ears: set wide and forward on forehead, alertly carried. Trivia:

Horses with lop ears are often said to

have a kind temperament, but beware of the exception to the rule.

Hair: an indicator of health; it should be fine, vigorous, with

natural sheen, and full in the tail.

Colors*

The solid colors are classed as follows.

Black (blk): a

rare color, not to be confused with very dark bay or brown; there are no light

areas.

Brown (br): brown horses may be anything from deep brown to

near-black, with light areas at muzzle and eyes.

Bay (b): a range of reddish hues from sandy bay (light

shades), to blood bay (red shades), to mahogany bay (dark shades);

distinguishing characteristic of bay horses is that mane and tail, and often

lower legs, are black, and ear tips are edged with black.

Chestnut (ch): a range of reddish brown hues, with mane and tail of

same color or lighter.

Gray (gr): a blending of white and black hairs; depending on

proportion of dark to light, horse may be a very dark gray or almost

white. At birth these animals are dark; they lighten gradually as they

mature.

White: true white is rare: such a horse is usually an albino.

Palomino (p): a range of golden colors, from cream to orange; mane

and tail should be lighter than the body, from silver to flaxen. White leg

markings are common.

Roan (rn): a fairly uniform mixture of hairs of different

colors: strawberry roan (chestnut with white hairs); blue roan

(black, white and red hairs); red roan (bay with white).

Dun (d): a range of dull tans including grayish mouse dun,

yellowish buckskin dun, and a creamy color called Isabella; all

have a black mane and tail.

Spotted or particolored horses are of two types:

Piebald (p.b.): black

and white.

Skewbald (skbld): white and any color except black.

*abbreviations are standard usage for show catalogs, etc.

Head Markings

Blaze: a

large patch of white on forehead.

Star: a small white patch on forehead.

Strip: a patch extending from forehead part-way down the face.

Stripe: a thin line of white extending from forehead to the nose or

lip. A "calf-faced" horse is one with a predominantly white

face.

Snip: a white or skin-colored spot on the lip or nose.

Leg Markings

Stocking: white

marking on leg as high as knee of the foreleg, or hock of hind leg.

Half-stocking: white on leg about midway to knee or hock.

Sock: white marking from hoof to fetlock.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Gaits

The way a horse steps or

runs is called a gait. The basic natural gaits are the walk, trot, and

gallop; in addition, there are many variations on these which horses can be

trained to perform. An aptitude for a certain gait has been responsible

for the development of many breeds. The Tennessee

Walking Horse is a prime

example of a horse bred for its gait; riding a sure-footed and restful Walker, a

man inspecting a plantation can spend an entire day in the saddle without

becoming tired and without damaging crops as he moves among the plant

rows. Another example is the Thoroughbred

race horse, developed for galloping

swiftly over comparatively short distances.

A gait may be generally termed as "high" or

"low." The Thoroughbred

has a "low" action--there

is only as much elevation of the feet as is needed for his great pendular

strides. The English Hackney

and the American

Saddle Horse have extremely

"high" actions that are intended mainly for show. These breeds

are exaggerated examples, however. With any horse, training is required to

develop poised and good-looking action, even in the walk. More extensive

training goes into developing highly styled, modified gaits, such as the canter

in place, the pace, and the rack. For certain gaits, such as the slow

canter, the rider "collects" his horse, controlling its impulse to

move freely. When collected, the horse appears poised, eager, coordinated,

and compact.

____________________________________________________________________________________

How Horses See

The horse's eyes are ideal for its existence as a

plains-dwelling, grass-eating prey animal, and are similar to those of other

prey animals, for example cattle and antelope. Such animals need the

widest possible field of vision so that they can see potential predators

approaching more or less from all directions. Their eyes are set on the

sides of the head, rather than at the front like predators such as cats, dogs

and humans. In their natural state grass-eaters spend a good 16 hours a

day with their heads down, grazing. This position (of the eyes) gives them

the ability to see all around with a small turn of the head whilst still eating,

without moving the body as humans need to do if they want to see clearly behind

them. The only obstruction to the horse's vision in this position is its

four thin legs, so it is ideally equipped for most of the time to spot

danger. This is the main reason for its good survival rate in the wild,

and explains why it is not easy to approach horses in a field without being

noticed.

The accompanying diagram (which isn't on this website yet!) shows the

horse's actual field of vision when it is looking straight ahead. Its

vision is mainly "monocular" (single-eyed), that is, it mostly sees

its surroundings as two pictures, one from each eye. This indicates that

it is probably capable of thinking about two things at once, at the same time as

grazing. It has "binocular" (two-eyed) vision directly in front

of it for judging clearly how far away an object is, and to enable it to assess

accurately the route in front of it when moving.

For many years the horse was described as having a

"ramped retina," because its retina (the screen at the back of the eye

on which rays of light carrying images focused) was thought to be sloped.

This would require the hose to move its head to bring the images into

focus. It is now (1990) known that the central part of the retina gives

the clearest picture, and this is the reason for the horse's various head

movements when trying to see something. It moves its head to direct the

rays through the eye lens (which is not so flexible as in human beings) to

direct them on to the center of the retina.

The most significant point to emerge is that in order for the

horse to have clear vision and, therefore, peace of mind and security, it must

have reasonable freedom to move its head and neck as it wishes. If the

rider restricts its head unduly, by means of either reins, or equipment such as

martingales which "strap down" the head, they are partially blinding

the horse. This is one reason why a horse not only goes unwillingly, but

may fight for its head. The other reason is that a horse naturally panics

if over-restricted. Freedom of its head and neck is particularly important

when a horse is moving fast or jumping, as it must have clear vision to

judge the ground, and the size of obstacles.

To see clearly close in front of it, the horse must arch its

neck and draw in its muzzle into a "collected" position. This

directs the rays of light through the top part of the pupil on to the center of

the retina. If you watch your horse, you'll see it do this to look at you

or something you are carrying when close to it, or to inspect some close-up

object or the ground in front of it.

The horse's pupil is a horizontal oval rather than a circle,

giving it a wide but rather shallow panoramic field of vision, and it can be

easily startled by things not quite in view above its head. Young horses

backed for the first time are often frightened by a rider sitting up above

them. It's advisable for the rider to crouch low over the withers at

first, gradually assuming a more upright position.

The inability to perceive depth, except when looking

immediately in front of it, accounts for the fact that the horse will shy

sideways away from something which startles it because it cannot tell what it

is. It will, if permitted, turn and face the object head on, from a safe

distance, look at it with both eyes and satisfy its curiosity.

It's keeping its eye on you

When you are riding, your horse can see your legs, whether or not you are carrying a whip, and when you move it to use it (which is why it may often anticipate your whip aid and move before you apply it). When you are riding a bend or a circle, its inside eye can make visual contact with yours, if you position the horse correctly, and you can just about look each other in the eye.

The horse's field of vision enables it to see almost all

around it. This gives it the advantage that while it is grazing, it only

has to turn its head slightly in order to check that there is no danger

approaching from any direction. It is almost impossible to approach

unnoticed.

The horse's eyes are set on the sides of its head, and it

sees two different pictures, one with each eye. This gives it a very wide

field of vision. The small V-shaped area directly in front of its head

(shown in diagram; not here) is the only area where it can see with both eyes

and therefore clearly judge distances.

The harness of draught horses usually incorporates blinkers

to prevent the horse from becoming alarmed by the traffic and other distracting

sights that usually surround it in a busy street. The blinkers of these

Shire horses belonging to a British brewery keep their attention focused on the

road ahead.

Glorious Technicolor

An old belief of some horsemen was that horses are color blind.

Research shows, however, that they do have similar color-discerning cells in

their eyes to those in humans. They can, it seems, see yellow best, and

orange and red. They can distinguish green quite well but have difficulty

with blue and violet. It is important to school your horse over different

colored jumps and use all the colors of the spectrum to accustom it to anything

it might meet in the jumping arena.

(There was a diagram with this paragraph that I need to

find. It showed the color spectrum in a series of rectangles--from red,

through orange, yellow, green, blue, and indigo, to violet. Then there a

line through the center of the red rectangle that connected to one that ran

along the top until it got to the center of the green rectangle--labeled

"horse spectrum"--and also to one that ran along the bottom all the

way to the violet rectangle--labeled "human spectrum." If you

know where I can find this, or any other diagrams, please contact me;

otherwise, I'll keep looking!)

____________________________________________________________________________________

How Horses Hear

Horses are very sensitive to sound, and can hear high- and

low-pitched noises that humans are unable to pick up.

The pinna, or funnel part of the ear, picks up the

sound waves and directs them down inside the head where a network of bones and

chambers together with the eardrum transmit and amplify them for special nerves

to pick up. These nerves in turn transmit these messages to the brain,

which translates the sounds into meaning if they are familiar, or alerts the

horse to something strange in its environment if they are not.

A horse does not automatically panic at an unfamiliar sound;

it will pay attention to it and remember it. If something happens at the

same time as the sound, it will, in future, associate the happening with that

sound, and this is an important part of training and learning.

Horses' hearing is sharper than that of humans; they can hear

things like other horses calling, car engines (which they can tell from each

other) and doors opening, before a person can pick them up and from much further

away. Horses that are boarded out, for example, soon come to recognize

their owners' car engines and associate the noise with the appearance of that

particular person. They will often pick up the sound long before the staff

in the stable.

Horses are extremely sensitive to the nature of a sound and

its volume. There is never any need to shout at a horse unless it is a

very dominant animal either attacking or really pushing its weight around, in

which case volume can help get the better of it. Tone of voice is

usually more effective than volume; a cross growl when the horse is doing wrong,

and an up-and-down, pleased tone for praise.

Screaming and screeching often frighten horses, whereas soft

monotones calm them down. However, some sounds which might be thought to

frighten them, such as blasting in a quarry or police sirens, do not always do

so.

Horses are as agitated by constant, raucous sound as humans

are. In racing stables, for instance, the best trainers insist on a quiet

period during the afternoon after morning work, grooming and the midday feed, so

that the horses can lie down and rest or have a sleep.

Some horses prefer a busy atmosphere where they can see and

hear what is going on around them, and others like peace and quiet. It is

important to watch your horse and try to tell by its behavior and expression

which category it falls into. If it seems slightly (or very) tense, its

ears flicking around a lot, not resting much during the day, it could be that

there is too much noise going on for its liking.

The position of the horse's ears on the sides of its head enables it to hear almost all around it. Each ear can pick up sounds to the front and side, leaving a gap immediately behind it which it can cover with a small turn of its head. (This picture isn't very good when it's downsized to fit this page, so I'll keep a lookout for a better one; still, it gets the point across!)

Music

Experiments carried out with mares at the Irish National Stud

some years ago showed that horses like music, but are selective in their

tastes. Most horses like calming or cheerful instrumental music and are

agitated by heavy, loud unmelodious music such as rock. Vocal music is

also not as welcome to them as instrumental music.

Dressage performed to music is now popular in many countries

and the horses really seem to enjoy it. They appear perky, majestic, calm

or energetic according to the music chosen for their routine. Like circus

horses, they often associate the music with particular movements.

Remember that your horse is a prisoner in its stall.

You may enjoy having a radio playing while you work, but see whether your horse

enjoys it as much as you do. Never leave a radio on all the time as it can

really get on a horse's nerves, and be selective about the programs you tune in

to, and the type of music played. The horse has to rely on you for both

its entertainment and its peace and quiet.

Love calling!

Another experiment done at the Irish National Stud was that of playing the sound of a stallion calling to an in-season mare to study the effect this had on the brood mares stabled in a particular barn. It was found that those in season and ready to mate showed signs of being amenable to the stallion even though he was not present, and those not in season came into season after a very few days of the sound being played to them intermittently.

(I don't have pictures to go with the following info yet, but

I'd like to find some.)

The mare has one ear back and one forward, indicating that

she is listening to what is going on all around. (With a picture of a mare

and foal.)

The horse on the right is interested in what is going on

around it, while its companion is showing signs of annoyance. (With two

white drafts--possibly Shires--pulling a brewery wagon--?etley?)

The language of ears

The position of the ears is one of the most important indicators of a

horse's mood and intentions. Ears pricked forward are a sign of alert

curiosity and good mood. Ears turned back are often a sign of relaxation,

or even boredom. They may also be a sign that the horse is unwell.

The ears pressed flat against the head are a classic sign of bad temper and

aggression. It can also signify that the horse is feeling stressed.

When the ears flop to either side, it may be a sign of sleepiness or

sickness. It is also a typical sign of submission to a more dominant

horse.

(This paragraph was accompanied by (and hopefully, will again

someday be accompanied by!) a diagram including four sketches of horseheads,

labeled, respectively--alert and interested; relaxed, bored or unwell; sleepy,

unwell, or submissive; and, angry and aggressive--according to the rules laid

out in the above paragraph.)

____________________________________________________________________________________

(Note: I chose to take the entire section below from its source—The Young Specialist Looks At Horses—because it was an older publication and had a lot of information that was somewhat unfamiliar and very interesting to me. The pictures also are taken from the same book. It may be noteworthy that this book was published in England.)

Conformation

The standard requirements regarding the exterior and interior of

the horse vary with the use for which the animal is intended.

Nevertheless, whatever the purpose, there are several basic requirements for

every horse. If we regard its overall shape, ignoring any minor external

defects (and a perfect horse is as rare as a perfect man!) it should embody the

ability to work and, if possible, the features of a particular breed. A

horse which bears the features of its breed indicates that it is pure bred, and

thus possesses its breed's basic qualities. Clean, well-defined lines,

well-defined muscles, sound foundation, conspicuous points and general noble

appearance enable us to draw conclusions as to its energy, courage, hardiness

and capacity for work.

We require our horses to have plenty of "scope,"

which means that the animal is distinguished by its good points. The

relationship of one part of the body to another is known as conformation; for

example, forequarters to hindquarters, length to height. At the same time

it means that long lines make up the contour of the horse, that the neck and

shoulders are long, the croup and pelvis broad and long, and the chest

deep. Thus, conformation is not just an absolute measure of size; for

instance, a pony may in certain circumstances "conform" in more

respects than a much larger and more powerful heavy horse.

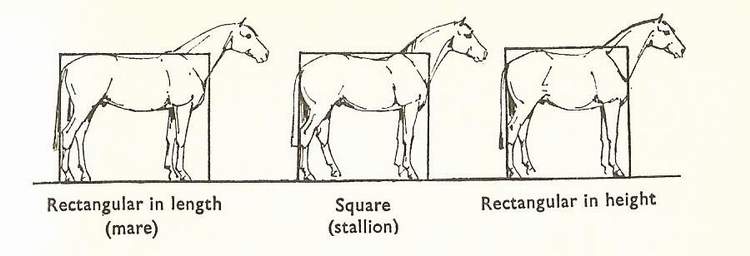

Two other terms used in judging horses must be defined.

Shape (format) and calibre. Format is understood to be the relation

between the length of the body from neck to rump, and its height at the

withers. This proportion varies with sex and breed. The stallion is

usually square, the mare rectangular in length and the gelding rectangular in

height. Breed also affects the shape, thus the percentage of square-shaped

animals of all three kinds is higher amongst the Orientals than in any other

breed.

Calibre is the ratio of weight to height.

Now let us examine the exterior of the horse in detail.

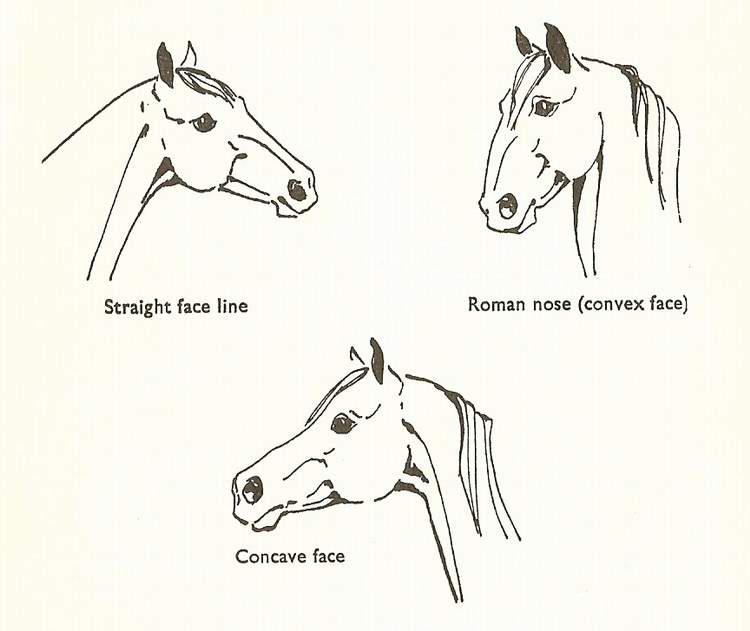

A small, well-developed light head is preferable to a large, inferior, and bulky

one, even though its effect on the intrinsic value is small. Alert, and

not too long, ears; large, clear, lively eyes, and wide nostrils, improve the

appearance of the head. Nonconformity with the breed is often to be found

in the profile of the nose, which may be straight, concave or convex.

The join between head and neck (cheeks) should be light and

fine. The neck itself should, however, be as muscular as possible, broad,

and not too short overall. A very short and thick neck, or one excessively

long and thin, will result in considerable difficulties for the rider.

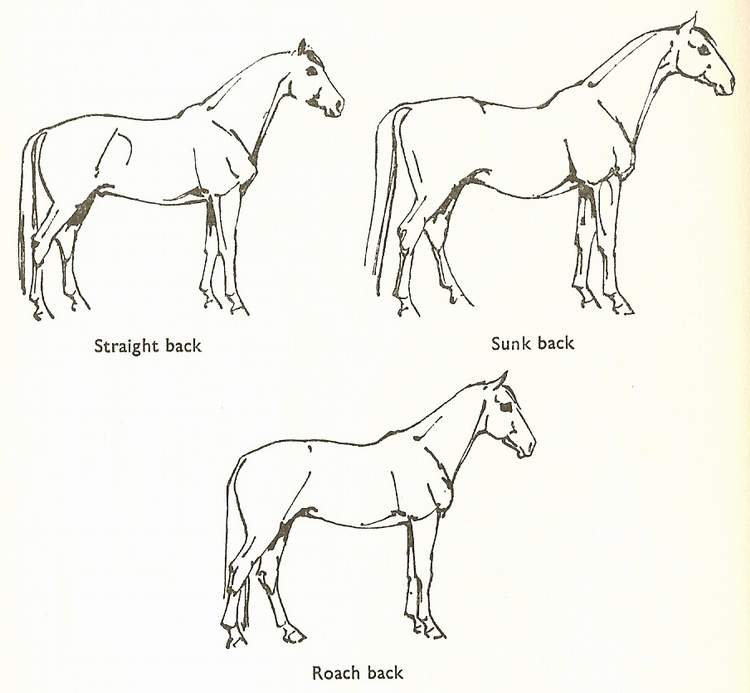

It is not so important for the withers to be specially high,

but they should be long and have strong muscles so that, along with an equally

muscular straight back and adequate barrel, a good foundation for the saddle is

assured. Faulty backs, such as roach-back or hollow back are unfavourable

for riding, and indicate a weak constitution. The horse should have

strong, muscular quarters.

The chest should be deep to give the heart and lungs plenty

of room to develop and work. The width of the chest is not so significant

and only of importance in draught horses.

The forelegs are connected to the shoulder by powerful

muscles. The arrangement of the shoulder muscles is the deciding factor

for action and stance. The longer, more sloping, and more heavily muscled

the shoulder blades are, the better the gait. The forearm should be almost

at right-angles to the shoulder-blade, and should be well-muscled. By

comparison, the cannon-bone should be short. The knee joint should be as

massive, broad, well-developed and defined as possible. The remarks

regarding the knees also apply to the fetlocks. A supple yet strong

fetlock, neither too long nor too short, and a healthy hoof with well developed

frog complete the picture.

As the impulse for all movements originates in the horse's

hindquarters, it, as well as the muscular connections to the horse's back, must

be as powerfully developed as possible. Broad, strong and firm loins are

able to transfer the energy and thrust from the rear foot, via the back, to the

forefoot. The croup comprises the greatest mass of muscle in the horse's

whole body. It should be long, broad, and well rounded—and its muscles should extend deep down

both inside and outside. The pelvis should be as long as possible and

sloping, with long thighs and strong buttocks. A plummet dropped from the

hip joint should strike the broad hock embedded in solid muscle. The same

also applies to the hock; it must be massive, broad, well-developed and

muscular. The cannons of the hind legs should be as short as

possible. A tail set and carried high completes the well-formed croup.

The movements of a horse with correct position of the fore

and hindquarters are far superior to those of a horse with irregular

extremities, as any defect automatically results in an inferior performance.

No horse is without some exterior imperfection but a good

interior can compensate for any of these shortcomings. (The opposite, however,

is not true!) The expression of the eyes, the set of the ears, the

carriage of the tail, his reactions to his surroundings, his participation in

what is going on around him, and the way he moves, reveal to us his mentality,

his temperament, his character, his intelligence and his willingness and

capacity to learn and work.

Colours and Markings of the Horse

Even though the colour of a horse has only a slight effect on

his intrinsic value, a detailed knowledge of the colours and markings is

essential for recognition and descriptive purposes.

The horse's outer skin is covered thickly all over with

hair. On the eyelids, in the nostrils and on the inside of the hind leg,

on the udders, or sheath, rectum and vulva, the hair is very fine. The

length and other characteristics of the coat covering the remainder of the

horse's body, depend on the breed (the better bred the horse, the finer and more

silky the coat), stable temperature, care, feeding and general well-being.

The hairs of the coat enter the skin at an angle, and over large areas they lie

in the same direction or grain, overlapping like roof slates. Thus they

act as a light rain repellent, and offer some protection against the wind.

The general direction of the grain runs from head to tail. Places at which

the hair meets from different directions—for instance, on the forehead, chest

and loins—are called whorls.

The horse changes its coat in spring and autumn. The

coat of a healthy horse is short, fine and shiny. The winter coat is long,

woolly and not so shiny. During the change of coat the horse is

susceptible to illness, and therefore needs plenty of care. Apart from the

periodical changes of coat the horse has developed, on several parts of its

body, longer and stronger hair which has special functions and which does not

change. The hair on the mane and tail is particularly long and strong and

has the special task of keeping away insects. The eyelashes protect the

eyes from dust, etc. The single sinus and feeler hairs on the mouth and

nostrils are particularly important for feeding.

Horses are designated, according to the colour of the hair,

as brown, chestnut, black, grey, dun, palomino, pinto, dapple or roan.

There are several different shades of bay, chestnut and grey.

Horses with a brown coat, black mane and black tail are

termed bay. Depending on the shade, a distinction is made between

bright-bay—which often has a black dorsal stripe—mahogany bay, red bay and brown. Bay

horses, apart from white markings, usually have black legs. Brown horses

are black with a brown muzzle and brown rims to the nostrils.

Chestnuts have golden-yellow to dark reddish-brown coats with

mane and tail of the same colour or lighter. According to the shade,

horses are described as light chestnut, golden chestnut or liver chestnut.

Those horses which are completely black, except for white

markings, are called black. A horse whose summer coat is jet black, but

more brownish black in winter is sometimes called a summer black.

Bays, chestnuts and blacks are called roans when odd white

hairs are distributed throughout the coat, and most frequently on the head, dock

and legs.

Greys, in contrast to albinos—also known as pink greys—are always born black, and only change colour

gradually, usually starting at the head. They become lighter in shade each

time they shed their coats, until they are almost completely white. This

process generally takes ten years to complete, depending to some extent on the

breed and the individual horse. In the completely transformed condition,

small or large dark patches may be found throughout the coat. Then one

speaks of dapple grey.

Isabellas and duns have a yellowish-cream coat, the true

Isabella horse having mane and tail of the same, or sometimes lighter,

shade. In certain circumstances they may even be white, as in the

palomino. The dun has a black mane and tail as well as black dorsal

stripes and black legs (e.g. Fjord

Pony). A mouse-grey horse with a dorsal stripe

and black legs is called a blue dun (e.g. Dülmen Wild Pony).

Piebalds and skewbalds are horses with fairly large

irregular-shaped patches, usually brown and black, often brown or black on white

background or vice versa (e.g. Shetland

Pony, Pinto).

Horses with a pink skin and silky white coat whose whole body

is covered with black or chocolate spots—about the size of the palm of the hand or

smaller, and round or oval in shape—are said to be spotted (e.g. Knabstrup, Appaloosa, Pinzgau).

White areas of various shapes and sizes on the head and legs

of the horse are called markings. The skin under such genuine markings is

likewise light in colour, and unpigmented. A sharp distinction must be

made between them and patches of white hair caused by pressure from the saddle

or harness, or other damage to the skin. The skin beneath such patches is

pigmented, and of the same shade as the region surrounding the patch.

White markings on the forehead have different names according

to their size and shape. White streaks of various lengths and widths

stretching from the forehead to the lips are known as blazes. The blaze

may be described as narrow, broad, irregular, broken or full, depending on its

size and form. The full blaze reaches down to the upper lip. A blaze

which also extends above the eyes is called a flash and is usually a condition

of wall-eye, or glass-eye. A bright spot on the upper lip is called a

snip. The muzzle may be either white or flesh-coloured.

On the limbs, distinctions are made between white coronets,

half-white or white fetlocks. White hair halfway up the cannon is termed a

"sock." If the white hair reaches up to the knees or hocks it is

called a "stocking."

The hoof horn, usually of dark pigmentation, is often

unpigmented when the limbs also carry white markings, or it may be light

coloured, pale-yellow or streaky. This is of some importance, for

unpigmented hair, skin or horn is, as a rule, less able to withstand external

influences than the pigmented.

The Mechanics of the Horse's Movements

As the horse only serves man when in motion, either under the

saddle, in harness, or as a beast of burden, it is of particular importance to

study and understand exactly the mechanics of his movements.

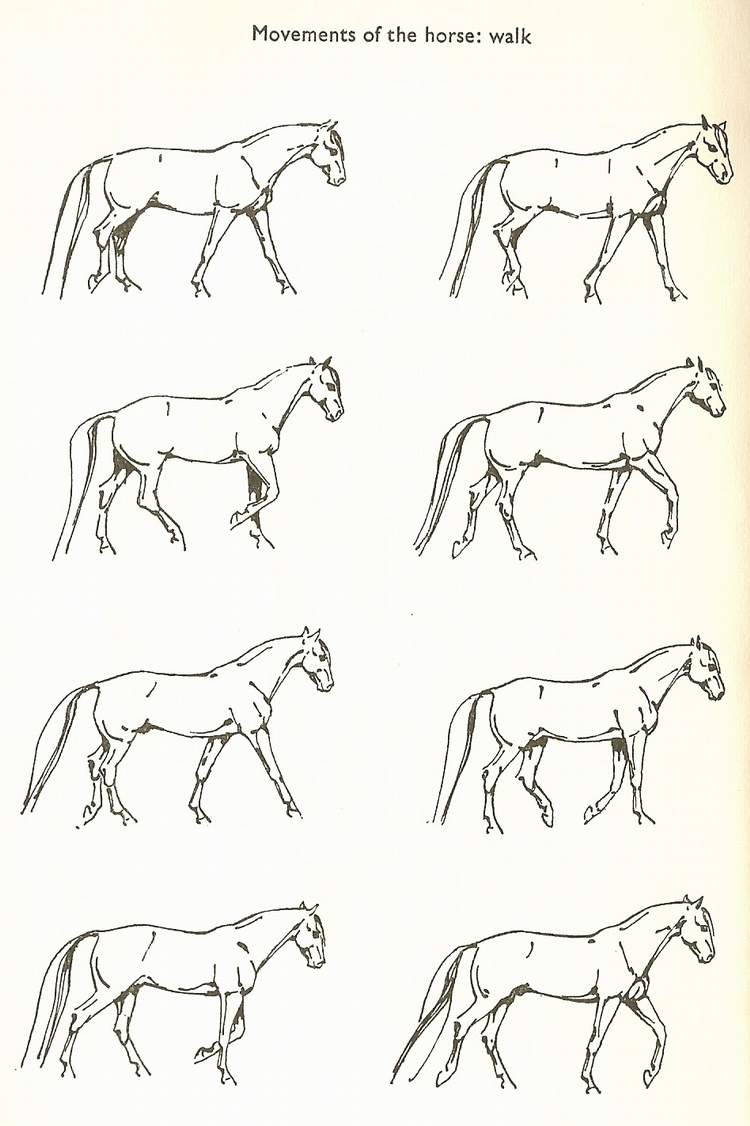

The natural gaits of the horse are divided into three: walk,

trot, and gallop (including canter and fast canter). For each of these

gaits, according to the length of the step, there are different strides.

The walk is the slowest gait. The feet strike

the ground with four distinct and separate hoof beats in a sequence which can be

clearly heard. Beginning with the near hindfoot, the following sequence is

observed:—

1.

Near hindfoot

2. Near

forefoot

3. Off

hindfoot

4. Off

forefoot

The near hindfoot leaves the ground when the off forefoot is

half way forward. The near forefoot leaves the ground as the off forefoot

lands. The near hindfoot lands as the off forefoot leaves the

ground. A distinction is made between the slow gait (middle step), in

which the hindfoot steps a hoof-length beyond the footprint of the forefoot; the

collected gait, in which the hindfoot lands a hoof-length behind the footprint

of the forefoot; and the extended gait, in which the hind foot lands two

hoof-lengths beyond the mark of the forefoot.

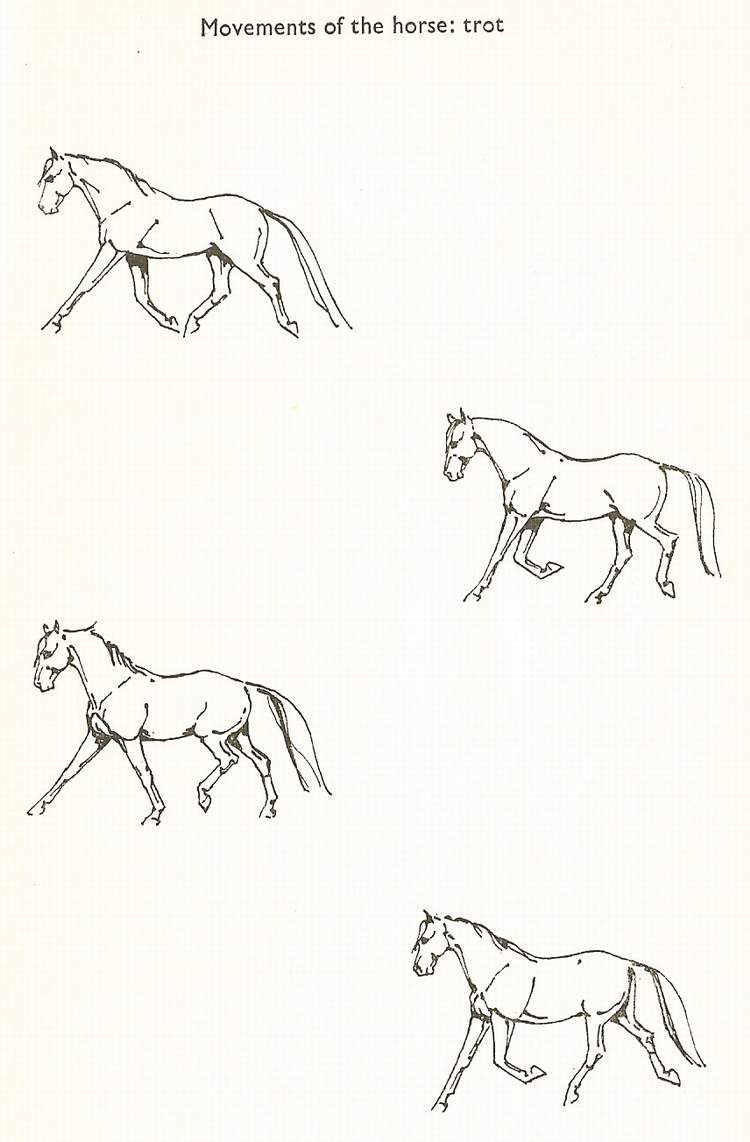

The trot is a quick manner of walking with a diagonal

foot sequence. The diagonally opposite pairs of legs leave the ground

regularly, so that the sound seems like that of only two hoof-beats. It

appears as if one pair of legs were still on the ground while the others are

elevated.

1. Near

hindfoot and off forefoot

2. Off

hindfoot and near forefoot

In actual fact there is a short interval between the movement

of each leg of the diagonal pairs, but it is so small that it can be

ignored. A distinction is made between the ordinary trot, in which the

hindfoot follows the tracks of the forefoot; the collected trot, one hoof-length

behind; and the medium and extended trots, one and two hoof-lengths respectively

beyond the track of the forefoot. In both the last named steps,

particularly in trotting races, there is a pause after each diagonal pair

strikes the ground, during which all four feet are off the ground.

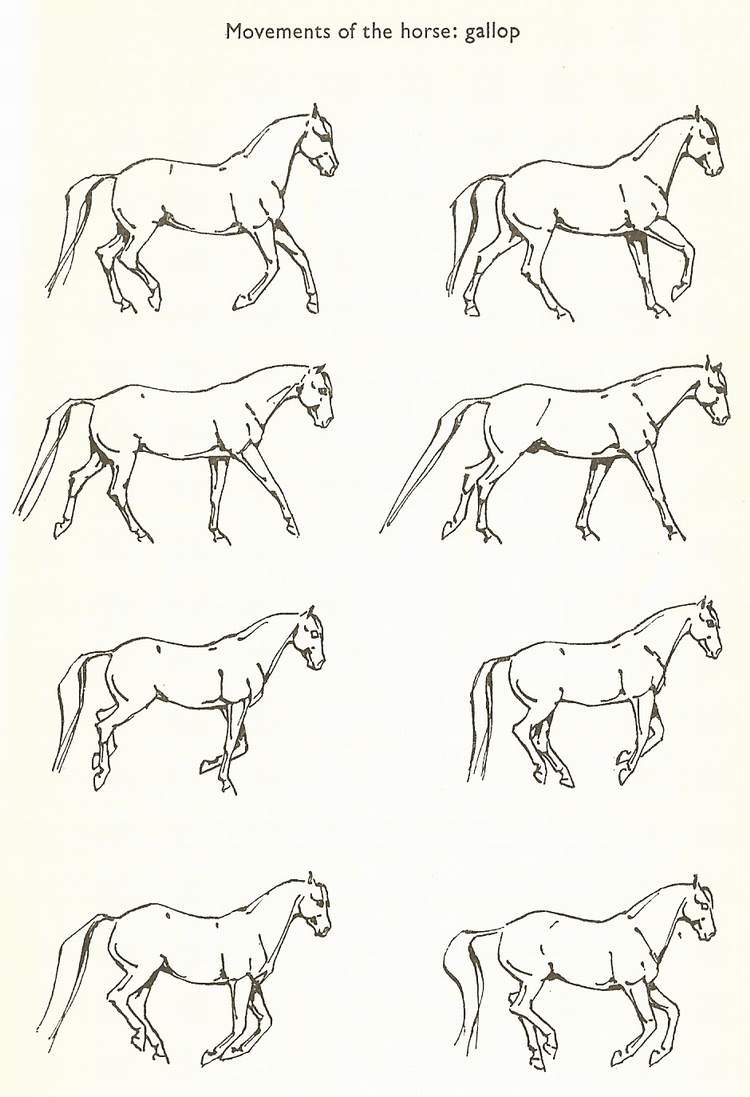

The gallop is the fastest of the horse's gaits, being

an extension of the canter. A distinction is drawn between a canter

to the right and a canter to the left, depending on whether the near or off

right pair of legs leads. In the canter to the left the sequence is as

follows:

1. Off

hindfoot

2. Near

hindfoot and right forefoot

3. Near

forefoot

4.

Interval

Thus, one hears a three-beat gait and then a pause. The

steps are distinguished as for the trot. In a faulty, foreshortened

canter, with too little elevation, the interval is lost and four beats are

heard. Therefore the following foot sequence is observed in the canter to

the left:

1. Off

hindfoot

2. Near

hindfoot

3. Off

forefoot

4. Near

forefoot

When cantering in this way, the horse is said to

"roll."

The pace, very popular in the Middle Ages because it

was considered comfortable, is now regarded as faulty and is cultivated only in

the five-gaited saddle horse in America; in the racing pacer, and a few mountain

breeds (pack ponies). The pace is a two-beat gait in which the lateral

legs move together, while the other two act as supports. Racing pacers

(flying pace) are distinguished from ordinary pacers only by the length of

stride and the more rapid succession of the individual steps.

Jumping over an obstacle is nothing more than a higher and

longer galloping jump.

The selection, which has taken place over a long period, to

obtain racing performance in certain gaits has brought a specific development in

the structure of various breeds. The high withers, long sloping shoulders,

powerful back muscles, the often absolutely ideal loins, and the long, sloping

croup of the Thoroughbred are a direct result of training and performance in

racing at the gallop over many generations. The development of the Trotter

took place in exactly the same way. The rigid rump required in trotting

racers, after several generations, brought about a degeneration of the back

muscles and the development of upright shoulders, low withers and the so-called

trotting pitch.

It is often possible to change from one gait to

another. A horse with a long walking stride always has a long galloping

stride.

____________________________________________________________________________________

(Note: I personally do not believe in evolution; however, I do recognize that the scientific classification of various species, etc, is generally legitimate and can be quite useful, so I have included the classification for the horse family here, as laid out in The Empire of Equus. This source can be found listed on my More Information page. It may be noteworthy that the author included a new subgenus which he proposed--it may be seen with his name, D. P. Willoughby, listed to its right as he showed it in the book.)

GENUS Equus Linnaeus, 1758

A. Equidae with unmarked (or very incompletely striped coats; a

mid-dorsal stripe in all wild forms and in certain breeds of domestic horses;

sometimes a shoulder stripe; sometimes zebra markings on limbs:

1. Subgenus Equus* (H. Smith, 1841)

a. Equus caballus caballus

C. Linnaeus, 1758 (domestic horse) Norway.

b. E. caballus przewalskii

M. Poliakov, 1881 (Przevalsky's horse; Mongolian wild horse) Desert of Dzungaria,

in the western Gobi.

c. E. caballus gmelini

O. Antonius, 1912 (tarpan; South Russian tarpan) Steppes of Ukrainia. Now

extinct except for "back-bred" zoo specimens.

2. Subgenus Hemionus (P. Pallas, 1775)

a. Equus hemionus hemionus

R. Lydekker, 1904 (kulan; kulon; chigetai; dziggetai) The Altai, in western

Mongolia.

b. E. hemionus kiang W.

Moorcroft, 1842 (kiang) The Ladakh range, in the western Himalayas (elev.

13,000-16,000 ft.)

c. E. hemionus onager P.

Boddaert, 1784 (Persian onager) Kasbin, N.W. Iran.

d. E. hemionus khur R.

Lesson, 1827 (Indian onager; ghor-khar) Kach.

e. E. hemippus I.

Geoffroy St. Hilaire, 1855 (hemippus; Syrian onager) Syria. Now extinct.

3. Subgenus Asinus (J. E. Gray, 1825)

a. Equus asinus asinus

C. Linnaeus, 1766 (domestic ass; donkey; jack; burro) Southern Asia.

b. E. asinus africanus

L. Fitzinger, 1857 (Nubian wild ass) Eastern Sudan.

c. E. asinus somaliensis T.

Noack, 1884 (Somali wild ass) Somaliland, district of Berbera.

B. Equidae with striped coats:

4. Subgenus Dolichohippus (E. Heller, 1912)

a. Equus grévyi E.

Oustalet, 1882 (Grévy's zebra) Abyssinia.

5. Subgenus Hippotigris (H. Smith, 1841)

a. Equus zebra zebra C.

Linnaeus, 1758 (mountain zebra; Cape mountain zebra) Certain mountain ranges in

the south or southeast districts of Cape Colony (formerly included Southwest

Africa also).

b. E. zebra hartmannae

P. Matschie, 1898 (Hartmann's zebra) Between the Hoanib and Unilab rivers,

Southwest Africa.

6. Subgenus Quaggoides, subgen. nov. (D. P.

Willoughby, 1966)

a. Equus burchelli burchelli

J. Gray, 1825 (Burchell's zebra; Dauw; Bontequagga) Plains of Cape Colony, south

of the Orange River.

b. E. burchelli böhmi

P. Matschie, 1892 (Böhm's zebra; including Grant's zebra) Pangani, on the east

coast of Tanganyika (now Tanzania) near the Kenya border.

c. E. burchelli selousi

R. Pocock, 1897 (Selous's zebra) Mashonaland and possibly eastward into

Mozambique south of the Zambesi (Zambezi) River.

d. E. burchelli antiquorum

H. Smith, 1841 (Damaraland zebra; Chapman's zebra) Southwest Africa, northern

part; including Benguella district of Angola.

e. E. quagga quagga J.

Gmelin, 1788 (quagga; Cape quagga) Now extinct; formerly the plains of Cape

Colony south of the Orange River.

f. E. occidentalis occidentalis

J. Leidy, 1865 (Western quagga) found in fossilized form in the tar-pits of

Rancho La Brea, Los Angeles California.

* Since the genus is also Equus, to avoid confusion the writer (Willoughby) prefers the name Caballus for Subgenus 1.

(The following note is taken from the paragraph that followed the above chart in Mr. Willoughby's book.)

The above list comprises only those equine forms described or reviewed in the present volume, and which can with some confidence be classified subgenerically. The number of named fossil species and subspecies of Equus NOT considered here is very large, possibly as many as a hundred forms.

(The following chart is taken from the above book also.)

Systematically expressed, the zoological classification of the common or domestic horse is as follows:

KINGDOM Animalia

(animals in general)

SUBKINGDOM Vertebrata

PHYLUM Chordata

(animals with backbones)

CLASS Mammalia

(warm-blooded animals that give milk to their young)

SUBCLASS Theria

(mammals that bring forth living young)

INFRACLASS Eutheria

(placental mammals. Excludes monotremes and most marsupials)

COHORT Ferungulata

(carnivores and hoofed mammals)

SUPERORDER Mesaxonia

(in which the leg is in line with the middle toe)

ORDER Perissodactyla

(odd-toed, non-ruminating, hoofed mammals, comprising the horse, tapir, and

rhinoceros)

SUBORDER Hippomorpha SUPERFAMILY

Equoidea

(of which the members of the horse family are the sole surviving

representatives)

FAMILY Equidae

(the Perissodactyla, exclusive of the tapir and the rhinoceros)

SUBFAMILY Equus GENUS Equus

(horses, zebras, asses, and hemionids)

SUBGENUS Equus

(true or caballine* equidae)

SPECIES Equus caballus

(existing or recently extinct forms include only the domestic horse,

Przevalsky's horse, and the tarpan)

SUBSPECIES Equus caballus caballus

(the domestic horse in all its breeds)

* By caballine is meant typical horses (those characterized by having broad hoofs and low, broad pelves), as contrasted with the narrow-hoofed, narrow-hipped zebras, asses, and the so-called Asiatic "half-asses" or hemionids.

(Note: The following is included as possibly helpful or at least interesting information. It is written, at least in part, from an evolutionary point of view, but the facts themselves are true.)

The various existing members of the horse

family (horses, zebras, asses, and hemionids) have these distinguishing

limb-bone and dental characters in common:

The digits, or toes, consist of a single functional one in

each foot, the digit III or cannon-bone; while the lateral digits II and IV are

represented by the splits (or splint-bones) alone. Hence, horses and their

kin walk upon the terminal bone of the third digit only, this bone being encased

during life in a large, solid hoof. To draw an analogy, in a human being

this would be equivalent to walking, not just on the two middle fingertips (or

toetips), but on the nails of these digits! In horses, what

corresponds to the human wrist is called "knee"; and what corresponds

to the human heel is called "hock"; and both these joints are located

high off the ground, giving to the horse its distinctively long limbs and

running ability. In true horses the hoofs are roundish, sometimes fully

circular; while in the zebras, asses, and hemionids they are elongate or

oval-shaped.

In all these animals the upper incisor (cutting) teeth number

three on each side, each tooth being chisel-shaped and slightly concave on the

distal (tongue) side. The canine teeth are developed only in males, and

are separated by a short space from the outer incisors and by a longer space,

called diastema, from the first premolars. The premolars in the

upper jaw usually number three on each side, but occasionally include a very

small additional one, PM1, present at the front end of the

tooth-row. In the lower jaw the number of teeth is the same, with the

exception that PM1 occurs only rarely. The premolars in each

tooth-row are normally three in number (PM2, PM3, and PM4),

as are also the molars (M1, M2, and M3).

Thus the tooth formula for males is normally 6 incisors, 2 canines, and 12

grinding teeth in each jaw, making a total of 40 teeth; while the number in

females, which lack canines, is 36. . . .

The premolar and molar teeth have high (vertically long)

crowns, which gradually push upward (or, in the upper jaw, downward) as they

wear with use. At one time it was believed (and is still occasionally

asserted) that the long-crowned teeth of horses grew continuously throughout

life, but now it is known that these teeth reach their full length at four or

five years of age. The continuous elevation of the occlusal (chewing)

surfaces of the teeth is caused by regular bone growth at the bottom of

the alveoli (tooth-sockets), which pushes the teeth outward and reduces the

depths of the sockets. The crown of each tooth thus shortens with wear

until the abraded surface reaches the neck of the teeth.

The limbs of equine animals are clearly adapted for swift

running over hard ground; and the teeth for cropping and masticating the coarse

grasses and other herbage of the open plains comprising these animals' natural

habitat. Foals are capable of rapid running within a few hours after

birth. Horses and their relatives are gregarious, and they breed once in

about every two years, normally giving birth to a single foal at a time.

Mares have two nipples, located on the lower abdomen. The winter coats of

horses grow in the fall, beginning about September, and are shed in the spring,

when they are replaced by short summer coats. The truly wild species and

subspecies assigned to the genus Equus, consisting of horses, zebras,

asses, and hemionids, are today found only in Asia and Africa.

Further to the foregoing general description of the existing

Equidae, the following particulars apply specifically to the domestic horse

(inclusive of its numerous varieties and breeds):

While the sexes are much alike in general appearance, males

(stallions) are slightly taller, heavier-boned, thicker-bodied, and generally

larger than females (mares). The necks, in particular, of stallions are

visibly thicker than those of mares, while the width of hips may be slightly

less. The greater docility of gelded males, and the circumstance that one

stallion can serve 80-100 mares has led to the practice of castrating almost all

yearling males (colts) except racehorses. A gelding loses neither strength

nor speed, but may to some extent lose endurance; and he does not have the

thick, high-crested neck of the stallion. As to the size and proportions

of a horse's body, they vary according to breed, especially as to whether the

individual is of "light horse" type or heavy draft build. . . .

Taking the Norwegian horse (specifically the Fjord pony* of

western Norway) as a valid representative of the type of domestic horse familiar

to Linnaeus, a listing of its principal physical characteristics would show

these points (some of which are in marked contrast to those of wild forms of Equus

caballus): head and ears relatively small; mane long and pendant, with a

forelock; tail-tuft long and more or less fully haired to the root; general

coloration dun (yellowish bay), with a dark mid-dorsal stripe running from tail

to forelock through the mane; legs below knees and hocks usually dark; hoofs

(especially those on the forelegs) broad and rounded; chestnuts small and

usually on all four legs; number of lumbar vertebrae usually 6.

Paleontologists, when comparing fossil equids with living

species, generally prefer to use the skeletal elements of wild equines rather

than domestic horses, on the premise that the domestic animals have been

appreciably altered by artificial selection and breeding. However, Otto

Antonius, a Viennese authority on the subject, points out that "Perhaps no

animal, except the camel, shows so little change of the skull due to

domestication as does the equid type." To this statement the writer

would add that the proportions of the limb bones, also, in domestic horses show

surprisingly little differentiation from those of Pleistocene species. In

fact, the modern Arabian horse--with the exception of its enlarged

hoofs--presents in the relative lengths of its limb bones proportions almost

identical to those which express the average of the entire genus Equus.

(Note: I have included this paragraph partly because it has useful

information despite the evolutionary references and also because I really think

it somewhat supports a creationistic point of view. No room or time to

illuminate on that thought right now though!)

* Various sources, including Webster's New International

Dictionary, define the term "pony" loosely as a horse not over 56 or

57 inches in height, although the so-called polo pony, which is a type rather

than a breed, may range up to 64 inches! The broncos, mustangs, and

cayuses (Indian ponies) of the western United States are sometimes called ponies

regardless of size. In Germany, where an effort has been made to be

systematic in the matter, the term "pony" is restricted to horses not

over 120 cm (47 1/4 inches) in withers (shoulder) height, while those that

measure between 121 cm (47.6 inches) and 147.3 cm (58 inches) are known as kleine

Pferden ("little horses").

____________________________________________________________________________________

Another chapter of the above-mentioned book, The Empire of

Equus, was on The Immediate Ancestors of the Domestic Horse. While I

can't say I agree with all of it, and while it is too in-depth to include much

here, I would like to draw some thoughts from it. I do recommend a reading

of the original when possible.

It seems that most, though not all, scholars believe that

modern horses descend from more than one root species or breed. Some

suggest that Przewalski's horse and/or the Tarpan are the main root(s).

Others suggest three possibilities. A Dr. Ewart felt that the three

ancestral forms, which he called the plateau or Celtic variety, the steppe

variety, and the forest variety, could be represented by the Connemara pony, the

Mongolian Wild Horse (Przewalski's), and the Norwegian Gudbrandsdal horse.

Another scholar, Duerst, replaced Ewart's Celtic type with a desert or oriental

type, while replacing the steppe type with a large draft-horse form native to

central Europe, and the forest type with one similar to the Celtic pony.

As if this weren't confusing enough, other scholars have had

other ideas, including one who had five different "originals" (not

described in detail in this book). One felt that the so-called

"forest tarpan" (described elsewhere, apparently) was probably the

ancestor of domestic horses in the east-central European region (Poland, Czech

Republic, etc.). Another referred to three ancestral types in Europe,

called the Northern, Southern, and Western groups, containing horses from

Scandinavia, the Near East and North Africa, and heavy European horses,

respectively.

At any rate, I think it's plain enough that there has always

been more than just one type of horse and whether evolution is true or, as I

believe, God chose to create several kinds of horses, it makes for a fascinating

study to see how these types have become the many breeds that exist today.