History of the Horse

"Wherever man

has left his footprint in the long ascent from barbarism to civilization,

we will find the hoofprint of a horse beside it."

—John

Trotwood Moore

This page is still rather disoriented! I have added quite a lot of information on it, but have not had a chance to sort it all out and put it in any kind of order yet. I hope to eventually get it in some semblance of order, either chronological or otherwise, but that will have to wait for now.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Last semester in college, I took a course in creation studies. The textbook, The Creation-Evolution Controversy by R. L. Wysong, was very helpful to my understanding and view of the origin of the horse. Following is some of the information found in that book, which is cited with copyright under More Information, along with a few sources that were cited in it that looked helpful.

T. Storer, a zoologist, admitted: "The real origin of horses is unknown." G. A. Kerkut, quoted in the book, said: "It is a matter of faith that the textbook pictures (of horse evolution) are true, or even that they are the best representations of the truth that are available to us at the present time." And an interesting observation in a picture caption of an American Miniature Yearling Stallion stated: Horses today vary from this size, and even smaller in Argentina, to the seven foot high, 3200 pound Clydesdales. Yet they are all considered fully horses. . . . Are these examples of evolution, or variety within a creationistic "kind"?

The best, however, at least for me, was a short section devoted specifically to the horse. I quote:

A classic proof for

evolution, displayed prominently in museums and evolutionary texts, is fossil

horses. The evolutionary tree begins with the tiny many-toed Eohippus and

ends with the modern day horses. But what is not brought to our attention,

for obvious reasons, is:

1. The sequence from small many-toed ancestors to large one-toed species

is nowhere found in the fossil record. Every imaginable contradiction to

the presumed order is found.

2. The Eohippus is almost identical to the African Hyrax. Both are

the size of rabbits, have four front toes and three rear toes and live in brush.

3. Two modern type horses, Equus nevadensis and Equus

occidentalis, have been found in the same geological strata as

Eohippus. Thus we have modern day type horses grazing side by side with

their precursors.

4. There are no gradations from one link to another. All suggested

links appear suddenly in the fossil record.

5. Some present-day Shire horses are known to have more than one toe per

foot but are still considered fully horses. Thus Westall of Durham

University, for one, concluded that the "evolution" of Eohippus to

Equus was all wrong.

Since the time the horse was domesticated by man, well before the time of recorded history, it has proved more useful and more important in the progress of civilization than any other animal. Horses pulled plows, carried armies to war, moved goods to market, and right up to the 20th century were man's primary means of transportation. The horse breeds of today descend from those cart horses and cavalry mounts of ancient civilizations and indeed from the earliest domesticated animals of the genus Equus.

When man learned to hunt and kill animals for food he developed a definite taste for horseflesh; at a single prehistoric campsite in France the skeletal remains of some 100,000 horses have been excavated. It was only when man became a stationary dweller and a herder of animals that he learned the value of the horse as a beast of burden. The horse's combination of strength, agility, and learning power made it far too useful to be slaughtered for food and far more versatile than animals that had earlier been domesticated, such as the ass and the ox. The earliest archaeological evidence of the horse as a domesticated animal dates to about 4000 B.C. This was in Sialk, a community on the western edge of the Persian desert.

As

early as the 800s BC, horses who stayed behind in Siberia were captured and

ridden by nomadic warriors called Scythians; considered symbols of wealth,

especially in the afterlife, these horses were buried with their bridles

intact. Farther south and almost a thousand years earlier, Hyksos invaders

introduced the horse-drawn chariot to Egypt. The Shang dynasty also used

chariots to establish control in China, as did the Aryans in India and the

warriors of Mycenae in Greece.

Not until 100 BC would horses begin to contribute to the

daily lives of their owners by performing simple tasks and providing ordinary

transportation.

In

1493, on his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus made room for

horses on the Nińa,

placing them in slings to take the weight off their feet so they could keep

their balance in rough seas. Upon arriving at the island of Hispaniola,

the horses were blindfolded and carefully hoisted from belowdeck, then lowered

into the water and guided ashore by men in small boats. Columbus

established ranches on the island for horse breeding, a venture made possible by

more than 100 mares exported from Spain.

On his third voyage, in 1498, Columbus carried 40 more

horses, and by 1500 the Spanish crown owned a thriving breedership on

Hispaniola. But this stock was not responsible for the spread of Spanish

horses across the Americas. That would be up to the conquistadors.

The arrival of English colonists in the 1600s brought about a dramatic change in the lives of North America's horses. Lighter than farm oxen, horses could cross frozen rivers in the harsh northeastern winter. Almost as strong as their bovine counterparts, they could be used as pack animals or harnessed to pull homemade wagons and sleds. And more nimble than any of their contemporaries, they managed to negotiate the narrow Indian paths that connected early settlements. Merchants on horseback, the only means of communication at the time, traveled these paths to reach families in need of schoolbooks, small tools, household items—and precious news from back home.

Paths widened into trails and then became roads (originally called "rodes," or horseback routes) along which posts were set up as relay stations for horses and their riders. Extending 250 miles north from New York, the Boston Post Road was put to use by the first mail carriers in 1673. A one-way trip took almost three weeks, mostly through wilderness, and each postrider stretched his horse's endurance to the limit. By the 18th century a horseback route called the King's Highway extended all the way south to the Carolinas, and thanks to postmaster general Benjamin Franklin, by 1789 there would be 26 riders delivering mail along more than 2,000 miles of post roads.

In the South, horses had jobs like pulling hogsheads of tobacco to the wharves for shipment abroad, but mostly they afforded fun for their owners. Family coaches were common, and "two on a horse"—a male rider with a female sitting behind him on a cushion called a pillion—was standard fare. Virginians, in particular, loved their horses. In 1724, one writer observed that it wasn't at all unusual for a Virginian to spend an entire morning, walking several miles through the woods, to round up a horse just to ride a mile or two into town.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Ever

since man first domesticated the horse, in the Middle and Far East around 3000

BC, he has been instrumental in distributing the different horse types around

the world.

The nomadic tribes of central Asia, who were probably the

first people to domesticate the horse, would have taken their horses with them

as they wandered across quite large areas of the continent. Conquering

tribes took horses with them to pull their chariots, and to use as pack animals.

When the Celts were driven into western Europe, and

eventually to Britain, they took their Tarpan-type

horses and crossed them with indigenous horses to produce the Celtic pony, which

they used to pull their chariots. In Britain, the Celtic pony provided the

basis of many of the modern native breeds.

The Romans brought many different types of horses to Britain,

including Friesian

horses from northern Europe, from

which the Dales

and Fell

ponies developed.

When the Moors invaded Europe, beginning in the 8th century,

they brought with them many thousands of horses of Arab

breeding, from which the Andalusian

and many other European breeds were

created.

In the 16th century the Spanish Conquistadores invaded

America, taking with them a variety of ornately caparisoned Iberian horses,

thereby re-introducing the horse into North America.

(The following may contain some reference to primitive or prehistoric times; I include it because it could have really happened--though in a different time frame than they allow.)

The

horse was domesticated in the Far East by early civilizations about 5,000 years

ago (around 3,000 BC). Some experts believe this took place in Asiatic

Russia and others in the ancient Fertile Crescent comprising Assyria and

Babylonia. However, Stone Age drawings on rocks and in caves have shown

what appears to be a head-collar of some kind, so it is possible that more

primitive peoples had some kind of control or influence over early horses.

The earliest widespread use of domesticated horses was as

pack and harness animals. It is likely that even at this early stage in

the history of the horse's domestication, the horse types diverged into harness

types and riding types in different parts of the world.

Man began to ride horses quite early on, but in war early

civilizations such as the Egyptians and Greeks used horses mainly to pull their

chariots. The Persians, however, were excellent horsemen, and by 500 BC,

had a powerful cavalry with horses able to carry heavy armor and weapons.

The ancient Greeks were good horsemen, but the Romans, who had mounted cavalry

were not especially so.

Although bridles and bits had been invented by the time of the Parthenon Frieze (477-432 BC), saddles had not. The Greeks were good horsemen, and took great interest in the best methods of training and riding horses. The above pictures are from the North Parthenon Frieze, slab XIXX with a man controlling a horse. Above left is a detail; a note from the source observed that the holes in the horse supported the now lost bronze reins.

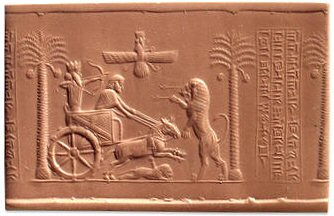

A Greek seal inscribed with the name of Darius I, who reigned from 548 to 486 BC. It depicts a king hunting from a horse-drawn chariot. Horses were used for drawing chariots long before they were ridden. The ancient Persians may have been the first to use the horse for riding. They were excellent horsemen, and developed a very efficient cavalry.

Trivia: The

most common type of Roman chariot to be used in races was drawn by four horses,

and was called the quadriga.

The earliest methods of harnessing animals always involved two animals, one on

either side of a central shaft. The idea of harnessing one animal between two

shafts did not appear to develop until the second century in China.

The Great Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, kept a herd of approximately

10,000 pure white mares, along with pure white stallions, and these horses were

treated as sacred.

In the Persian epic Shah Namah, Book of Kings, the

chief hero, Rustam, rode a horse called Rakush, who was reputed to be the best

warhorse in the world.

The Celts regarded the horse as a sacred animal in

their beliefs.

The amazing tomb of

Qin Shi Huang, 259 BC to 210 BC, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty contains

over 500 terracotta models of chariots horses, and 116 terracotta cavalry

horses. The terracotta models show great detail, with the manes clipped and

braided, and the horses standing around 17 hands.

Han Kan was a famous artist of the T'ang Dynasty, 618-906 AD

and was the court and horse painter to the Emperor Hsuan-Tsung, who is believed

to have owned approximately 40,000 horses.