Care of the Horse

"If you have seen

nothing but the beauty of their markings and limbs, their true beauty is hidden

from you."

~ Al Mutannabbi, 9th century A.D.

If you want to know how to take care of your horse (or other equine), this will eventually be the place you will find information. I don't intent to give a set of rules that will go for every animal; just some guidelines that hopefully hold true for all. If you already own horses (or other equines), and can give me some information about what you do, please contact me. For now, I will include some basic information about the horse on this page, until I decide where I want to put it. ____________________________________________________________________________________

The average life span of a horse is about 15 years, and the

age is calculated from January 1, regardless of what time of year the animal was

born. By the time a young horse is 12 months old, it will have reached

about one-half its adult weight. It will continue to grow and develop

until it is 5 years old, one year of a man's life equaling 3 years of a horse's.

Many horses live--and work--until they are 30 years old or more.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Life History

A horse

is born after a gestation period of 11 months. Within a half hour or so

after birth, the long-legged baby learns to stand up and to feed on its mother's

milk, its chief nourishment for about the first six months of life. After

this, as a "weanling," it has its milk teeth and feeds on grains and

grass. Growth continues to age five and full weight is reached at

seven. From weaning through age four, the young female is called a filly,

the male a colt; after that they become mare and horse (or stallion)

respectively.

Properly handled and cared for, a horse should be fully

serviceable for perhaps ten or more years after reaching maturity. Since

it ages at the rate of three years for every one in the human life span, at 21

it is the equal in age of a 63-year-old man. A horse that lives past

30--as some do--is in extreme old age. Trivia: The

oldest horse recorded was Old Billy. Foaled in 1760, he died on November 27,

1822, having reached an incredible 62 years of age. The

oldest Thoroughbred racehorse was Tango Duke. Foaled in 1935, he died on January

25, 1978 at the age of 42. Old horses will often grow white hairs around

the face and their muzzle.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Feeding

What foods?

The horse is a plant-eating animal, eating hay or oats with

its lips and grass by biting the blades off with its teeth. Its stomach

can hold 18 quarts of food, stored in its intestines.

If you keep your

pony in a field, it may need no extra food

during the summer, providing there is plenty of good grass; but watch that it

doesn't overeat. During the winter, when the grass has stopped growing and is

very poor, your pony may need up to 12 pounds of hay a day, and even more in

frosty or snowy weather.

Trivia: It takes about three days for a horse to

digest an oat. Feeding garlic to horses is believed to

help combat some worms, repel flies, aid respiratory disorders, and have a

cleansing effect of blood. There is, however, no scientific evidence to prove

this, and it does cause halitosis (chronic bad breath).

Grains and Short Feeds: As well as grass or hay, a pony may need high protein "short" feeds. These are a mixture of corn or cubes and a bulk food like bran or chaff. Put short feeds in a manger or galvanized bin.

You can use these foods to make up a short feed for your pony:

Bran: Mix bran into a feed with corn or cubes. It will make your pony eat more slowly and digest its food better.

Chaff: Chopped hay. Use chaff in the same way as bran.

Corn: Oats or barley. Oats is the standard grain, because it is easy to digest and it contains the elements that a horse needs most. Use crushed or split oats rather than whole oats. Barley is more fattening but has less food value than oats. Use either crushed barley, or whole barley boiled for two to three hours.

Cubes: Animal food firms sell different kinds of cubes (also called "nuts"). Read the feeding instructions on the sack carefully.

Flaked maize (American "Corn"): Corn is especially good for providing energy, but it is hard to digest. It should be given in small amounts to the heavier working breeds. A rich and rather fattening food, unsuitable for small ponies.

Linseed: Occasionally give your pony small amounts of boiled linseed; it has good food value and will improve your pony's coat.

Sugar beet: Good for fattening ponies up. Soak it in water for 24 hours before feeding.

Vegetables: If there is no grass, give your pony fresh root vegetables, or green leaves like sprouts or cabbage leaves. Chop carrots, mangolds, turnips and parsnips lengthwise before adding them to the feed.

Wheat: Wheat should never exceed 15 percent of the total grain consumption, as it is hard to digest.

Bran, linseed meal, cottonseed meal and soy bean oil are rich in protein and should be given in small amounts daily.

Sliced carrots are a welcome addition to an animal's diet.

Grass: Horses should be able to graze several hours a day. Grass is nutritious and need be the only food of a non-working horse.

Hay: A horse kept in a stable eats hay instead of grass. In winter all horses need, within reason, as much good hay as they will eat. The best type of hay is meadow or mixture hay--alfalfa, clover and timothy. Put hay in a rack or hay net to prevent it being wasted. Nets should be hung high enough not to entangle the feet when empty.

Salt: Remember to leave a salt or mineral lick (block) in your pony's field or stable. A horse should have one to two ounces of salt each day.

Water: It is preferable to give water to a horse before it eats. Special care should be taken if a horse is unusually overheated. Give it one swallow at a time until it is satisfied. But remember: You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make it drink!

How much?

Each horse and pony will need different amounts of food. How much

depends on temperament,

size and health, how much work the animal has to do, the time of year, where it is

kept, how much good grass is available, and how much the it has to eat to keep

its weight up. In their natural environment, horses and ponies eat

small amounts of bulk food (mostly grass) almost nonstop throughout the

day. Stabled animals need three

meals a day, at regular intervals, the largest, including most of the hay

ration, at night.

The general rule is to feed a horse 1 1/4 pounds of hay and

1/2 to 3/4 pounds of grain for every 100 pounds it weighs. If the horse

does not work hard, it should be fed more hay and less grain. Most ponies, and some horses, need their summer grazing

restricted in order to maintain the proper weight. They can be shut in by

day and given a few hours of grazing in the evening with water always available

and, if competing, some concentrated feeding such as cubes or oats, etc.

How to feed?

These are the basic rules for feeding a horse or pony:

Make sure it always has enough grass or hay to eat.

Feed it little and often. Horses and ponies have small stomachs, so they can't digest large meals properly.

Give it water to drink before you feed it, not afterwards.

Never ride it straight after a feed; wait about an hour.

Feed it at the same time every day.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Grooming

Grooming should be done daily. In winter, the grease in the coat keeps out the wet, and profuse manes and tails help maintain warmth. Shaggy coats can hide poor condition, and thin horses and ponies are cold ones. Healthy animals have bright eyes, skins that move easily under the hand, and are willing and interested in their work. Brushing removes dirt and dandruff while helping to keep the coat shiny. Areas touched by the saddle and girth need special attention. Trivia: Horses will generally begin to grow their winter coats in September, when the hair thickens and becomes coarser and dull. This gives rise to the saying, "no horse looks well at blackberry time." When clipping a horse's coat, the first clip is usually done in October and the last clip should not be done any later than the last week of January. Clipping after this time will affect the spring coat growing through.

The usual grooming routine is as follows:

Pick out its feet with a hoof pick, pulling the pick from heel to toe.

If your pony has a full coat, take off dirt and stains with a dandy brush, working back from the top of its neck. Always brush in the direction the coat lies.

Next, clean its skin and coat with the body brush. This brush has short, soft hairs. Clean the brush by pulling it across a metal or rubber currycomb. Brush the pony's head with the body brush, too, taking care not to knock it. The body brush is also used to brush its mane and tail. If you comb its mane with a mane comb, do it carefully, as the hairs will break very easily.

Clean its eyes, nostrils and dock with a damp sponge.

Brush around and under its hooves with hoof oil.

Wipe it all over with a clean cloth to make its coat gleam; as a finishing touch, smooth down its mane and tail with a damp brush.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Shoeing

Most working horses and ponies

need to wear metal horseshoes, to keep their feet from getting worn down.

Shoes also keep the hoof from becoming cracked, bruised or out of shape. If

a horse or pony works a lot, it will need new shoes every six

weeks. In that time, the shoes may wear smooth, and the animal's feet will

grow out of them.

Horseshoes must be made to fit properly. The blacksmith

(or farrier) takes the old shoe off first. Then he trims down the wall of

the hoof and fits a new shoe. The shoe will fit better if it is hot and

pliable. The shoe is nailed to the wall of the hoof where it won't hurt

the pony. Finally, the blacksmith files the surface of the shoe smooth.

Trivia: When a horse or pony

loses a shoe, it is sometimes said to have "thrown a shoe."

Horses' hooves grow approximately 0.25 in a month, and take nearly a year to

grow from the coronet band to the ground.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Housing

Crossbred ponies are physically and

mentally adapted to living outside all year, but "blood" ponies and most horses,

especially Thoroughbreds

and Arabians, do not thrive wintering out and should

not be expected to do it. Stabled animals, however, do entail both extra

work and expense.

To be fully fit and conditioned, show horses and ponies and

show-jumpers, should be stabled during the season - although an occasional hour

night-grazing is beneficial. The "stars" are normally roughed off for the

winter, and then only stabled at night. Full-time hunters summer out and

winter in. The general "all-rounders" can be stabled, according to work

and weather.

Animals that have been clipped can go out for a few hours in suitable winter

weather, provided they wear blankets, which are adequate covering for most

days. This works well if the horse is trace-clipped (the hair removed only

from under the neck, sides and belly). Stabled horses sometimes wear cotton summer sheets. For

winter they need a lined blanket. Blankets buckle across the chest and

must not strain over the withers.

Field?

In the wild, horses and ponies live in herds; they move about a great deal, grazing and drinking, and rest for only a few hours at night. There are many things they may miss in captivity. If you keep your pony in a field, try to give it:

Other horses or ponies to keep it company.

Good grazing. At least one acre of good grass or, better yet, several acres of rough pasture. You may need to change fields in spring or fall, to let the grass grow again. Pick up manure to stop worms from spreading.

Plenty of fresh water to drink.

Shelter. Trees, thick hedges or an open shed. Keep a salt or mineral block in the shed.

Fencing should be high and strong. A post-and-rail, wood fence is best. Wire is all right if it is tightly fixed to strong posts, with the bottom wire at least 18 inches from the ground. If of barbed wire, it must be taut, the bottom strand not more than 18 inches from the ground.

Horses kept outside cannot be as fit as stabled animals, nor capable of the same work. They come of stock used to a wide range of varied and sometimes scanty grazing. Lush, clover leys will make them very fat, and susceptible to Laminitis, a painful foot fever.

Stable?

It isn't natural for ponies to live indoors. If you keep your pony in a stable, it will need special care. It will need:

Regular exercise, roughly two hours per day, with a day's rest after strenuous hunting or competing. Turning out in a blanket for a few hours can replace some of the riding exercise.

Proper feed. A pony needs plenty of bulk food, like hay, to nibble during the day and night. It also needs short food, like oats, in small amounts, in the morning, at night, and perhaps at midday.

Plenty of fresh water.

A roomy stall (measuring at least 10 feet by 10 feet). Draft-free and well ventilated, with drainage, or a soak-away earth floor. The top halves of the stable doors should remain open unless it is bitterly cold.

A clean stall! Twice-daily "mucking-out" is a necessity. Clear out wet straw and droppings to stop bad smells and thrush (foot disease).

Good bedding. Conventional daily renewed bedding, at least a foot thick, is either wheat or barley straw (combine harvesting removes the prickles), sawdust or wood shavings (which are good) or peat (more expensive but lasts longer). Oat-straw bedding usually gets eaten. The bed must be thick enough to keep the pony warm and keep it from hurting itself. Advice should be sought on deep-litter--which generates sufficient heat to dry off the top layer and with daily removal of droppings, can stay put for months at a time.

Daily grooming. This will keep its coat clean and its skin healthy.

Blankets. If it has a full coat, one blanket will do. If it has been clipped, it will need two blankets. An extra blanket should be available to provide needed warmth.

Fresh air. Let it into the stable to keep your pony from getting coughs and colds. To avoid drafts, it is best if the window and door are on the same side of the stable.

If you want to change your

pony's feeding or exercise pattern, do it gradually. Ponies need time to

get used to new routines.

____________________________________________________________________________________

How Horses Sleep

Horses need sleep just as

much as humans do, but they don't need the same amount. They need about 4

hours sleep out of every 24, and take it in roughly half-hour snatches rather

than all in one go. The reason for this is, again, their prey/predator

lifestyle, which so frequently spills over into domesticity. As creatures

of wide open spaces, often with little natural protection such as a lair or den,

the horse needs to be constantly on the alert for danger. If it were to

spend several hours at a stretch deeply asleep, it would be easy prey for a

hunting animal, so it has evolved to sleep for short periods.

The horse does not always sleep at night, but takes

some of its sleep during daylight, if allowed to. Many horses that have

had morning exercise like to lie down for a nap after their midday feed,

imitating the sleep pattern they would adopt in the wild. This can also be

seen in horses turned out in fields, who often lie down during the day.

Apart from

dozing, there are two kinds of sleep, SWS (short wave sleep) and REM (rapid eye

movement) sleep. Experiments using electrodes to detect electrical brain

waves have shown that in shallow sleep the brain waves are of a short frequency

(SWS): the brain is quite inactive but the sleep is fairly shallow and the

horse can be easily awakened.

Deep sleep is

experienced when the brain waves are longer. The brain is active during

this type of sleep, but the body goes almost into a torpor, making the horse

easy to approach but difficult to wake up. During this sleep, the eyes

move rapidly from side to side beneath the eyelids, which is why it is called

rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Because the body seems to lose muscle tone

during REM sleep, the horse has to lie completely relaxed and flat out on its

side in order to experience it, whereas in SWS it can sleep propped on its

breastbone. It is likely that horses, like humans, dream during REM sleep.

Lying flat out is obviously dangerous in the wild as it takes

a horse several vital seconds to get to its feet and gallop off. It is

much safer for the horse to lie propped up as it can get up much more quickly.

From a management point of view, it is essential to give a

horse a large enough stall to allow it to lie flat out and experience the deep,

refreshing and essential REM sleep, and to give it a dry, clean, soft bed so it

won't be reluctant to lie down and rest. The horse must have enough room

that it does not become cast, which happens when it rolls over and becomes

trapped on its back because its legs strike the wall of the stall. Horses

always pick a smooth, dry spot to sleep when they have a choice:

those kept on wet land in winter may be reluctant to lie down often enough,

particularly flat out, and may deprive themselves of sleep as a result.

Such horses should have access to a well bedded down, roomy run-in barn or large

shelter.

Can horses sleep standing up?

Yes, they can and

do. Again, this is a safety feature from the wild. If they are

already on their feet (in which position they can either doze or experience SWS)

they can be off at a gallop within a couple of seconds of being alerted, usually

by other horses or by a sound.

There is a special arrangement of "locking" joints

and ligaments in their elbows and stifles (another safety feature) which props

the horse on its forelegs keeping it upright. It can rest one hind leg

(joints bent, hip down) during this process and still not fall over, but not a

foreleg. When alerted, up comes its head throwing the weight on to its

hindquarters, which gather underneath it ready to propel it forward out of

danger.

In this position

(standing up) a horse will doze, and can also experience short-wave sleep (SWS),

a shallow kind of sleep. To be able to sleep standing up was a great

advantage to the horse in the wild, because it could be off at a gallop within

seconds.

Horses need to lie flat out in order to experience REM (rapid

eye movement) or deep sleep. Horses whose stalls are too small, or who

feel that they don't have room to lie out like this may deprive themselves of

this type of sleep, and become over-tired, short-tempered or even neurotic as a

result.

Horses have a special arrangement of "locking"

joints and ligaments in their elbows and stifles. When the horse sleeps

standing up, these joints lock, propping up the horse on its forehand. It

can even relax one hind leg and still not fall over.

____________________________________________________________________________________

(Note: I chose to take the entire section below from its source—The Young Specialist Looks At Horses—because it was an older publication and had a lot of information that was somewhat unfamiliar and very interesting to me. The picture is also taken from the same book. It may be noteworthy that this book was published in England.)

Feeding

The correct feeding and maintenance of the horse, dependant upon

the work it is called upon to do, should certainly be one of the most important

tasks to be undertaken by the owner who wishes to preserve the intrinsic value

of the animal, and to enjoy possessing it for as long a period as possible.

Of all the feeding stuffs, oats most decidedly take

pride of place. Indeed, they can hardly be replaced by any other fodder

over a long period without doing harm to the working horse. Good quality

oats are bulky, dry, polished, and have no unpleasant smell; the grains are

uniform in size. Generally they are given whole. Oats should be

crushed only for young horses while they are changing their teeth, or for old,

or very run-down horses; otherwise they may become mouldy and musty, and so

cause colic. The amount of oats given varies according to the age and work

of the horse. Bloodstock, carrying out strenuous work, requires more

energy-giving fodder than a heavy animal, as much more work is required of

it. The heavy horse must, on the other hand, receive more raw

fodder. Horses which bolt their food are fed a mixture of oats and chopped

rye or wheat straw, as they then chew it more thoroughly. A few pebbles

about the size of the fist may be placed in the feeding trough to force the

horse to sort out the oats, and so eat more slowly.

To some extent, oats may be replaced by other fodder. Barley

and maize are particularly suitable, but from the horse's point of view

there is no fodder which he likes better than oats.

An excellent addition to oats for hardworking horses, race

horses in training, or hunters during the season, is the so-called mash.

Boiling water is poured over bran, perhaps with some linseed added, allowed to

cool, and given lukewarm. Equally recommended for horses which decline to

take food because of exhaustion is gruel, an oatmeal drink made from a

few handfuls of oatmeal dissolved in a few pints of warm water. Molasses

can be given where the animal is suffering from loss of appetite; it is very

nourishing and has a high sugar content. Usually, however, the animal

sweats more after having molasses than it does when working.

Apart from the energy-giving feeds, the horse's digestive

tract requires adequate amounts of fresh forage, to enable it to function

properly. A good hay is they most important in this respect,

besides which, it is essential because of its mineral content. Good hay

should be bleached green in colour, of crisp, coarse structure, and have a sweet

aroma. Clover and timothy grass are particularly nutritious, though too

much is inclined to be fattening.

Extra vitamins are not so essential for the horse as

for other domestic animals, as he is able to derive nearly all he needs from his

food. Moreover, the addition of a few carrots each day is an

excellent stimulant to his digestion.

If, despite adequate daily work, and hence not through

boredom, the horse is seen to lick the walls of his stall or box, the cause is

usually to be found in a shortage of minerals. This can best be remedied

by giving him a salt-brick to lick.

There is a widespread belief that the horse should only be

given water which has been standing for some time. But horses, like human

beings, much prefer to drink fresh water. The danger of catching a

chill, through drinking when he enters the stable still hot from his work, can

be avoided by laying a bundle of hay over the water, or by leaving the bit in

place to make the horse drink more slowly. Generally he is watered before

feeding.

The horse should be fed, if possible, three or even four

times a day, the largest portion being given in the evening so that he has

plenty of time to digest it during the night. During feeding there must be

absolute quietness in the stable. Such tasks as grooming and cleaning out

the dung should be postponed, so as not to disturb the horse and distract his

attention from his food.

Although it might appear that grazing would be the

only correct way, physiologically, of feeding, this method is not good for the

working horse. His efficiency will fall off due to lack of carbohydrates

and his digestive organs will be distended by the volume of food, as quality

will be replaced by quantity. Old horses unused to pasture, also suffer in

particular from cold and heat, insects, hard ground, etc. Grazing,

however, is essential for rearing foals, pregnant mares, or mares feeding their

foals. It is also recommended for horses with leg and hoof trouble.

These two, however, must also be given energy-giving fodder.

General Care

When building the stall or stable, it is important to remember

that this is where the horse will often have to spend nine-tenths of his

life. Try to make it as comfortably pleasant as possible, so that he does

not become dull. Above all the stall must be bright, well-ventilated and

free from draughts. Ammonia vapour damages the horse's lungs, so a good

manure gutter must be provided, and the manure barrow should be kept outside the

stable. If possible, the horse should be given ample room to move about,

by providing a sufficiently large box, preferably one permitting him to

look out of the door. If he must be tethered, the rope should not be too

long, otherwise he may become entangled should he paw the ground or scratch his

head with his hind leg. The side-walls or posts should be covered with

coconut matting or straw, to prevent the horse from hurting himself if he should

kick.

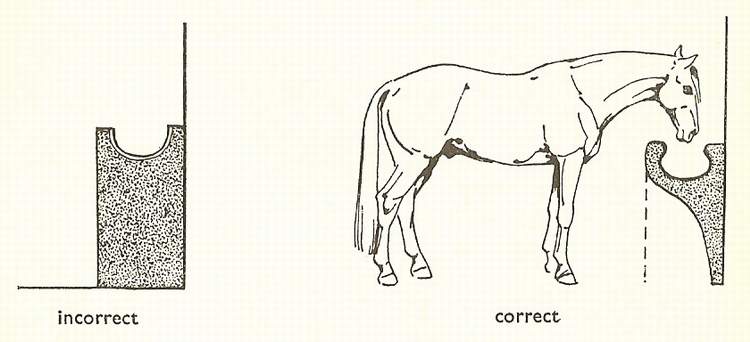

A shaped manger, extending inwards, is useful in

preventing the horse from spilling his oats, but it should not be fixed too

high, as this may cause the back of a young horse to sag; nor should it be fixed

too low, otherwise a temperamental horse may damage his knees by knocking

against it when feeding. Hay-racks are best located close to the

manger, with the bars close together so that the horse cannot catch his hoof in

them. A hay-rack located above the manger is as unsatisfactory as too high

a manger; besides this, the horse's head will always be covered in dust and

stubble.

The usual kinds of bedding for horses are either peat,

sawdust or straw, and the general practice is to clean the stable floors daily

by taking out the manure from the clean bedding, sweeping up the floor and

replacing the clean straw, adding fresh straw where necessary. Clean, dry

wheat straw provides the most satisfactory and warmest litter, and it should be

amply laid to a depth of at least six inches. Barley and oat straw are not

satisfactory, both break easily into chaff and the barley awns are apt to get

into the horse's skin, ears and eyes. Abroad, the system of deep-litter

bedding is often practised, and the wisdom or otherwise of this has aroused

quite a lot of discussion in Britain. This means that the entire bedding

is cleaned out only every two months or so, but whilst additional clean straw is

added daily, droppings should be removed as often as possible and it is also

necessary to fork out the middle part of the litter in the case of geldings and

stallions and the end part in the case of mares, and to replace with fresh clean

straw.

These are two methods of management for stabled horses; the

former was always used by the old-time grooms and is still practised in most

well-run stables today where there is sufficient help to ensure

efficiency. The second method was originally practised not through

shortage of labour but because the warmth of a clean deep-litter bed is

necessary for the well-being of the animals in the usually very cold Continental

winters (Great Britain has the advantage of the Gulf Stream) and, secondly, it

is a satisfactory way of making manure. If the actual dung is frequently

removed there is no reason why the horse's feet should become diseased or

damaged, since they should be cleaned and scrubbed daily whichever method is

used.

Daily grooming of the horse with body brush and curry

comb is carried out for two reasons. Firstly it clears the skin of dust,

dirt, and skin excretions such as sweat and dandruff. Secondly, this daily

massage stimulates the circulation of the blood through the skin and the

subcutaneous tissues and ensures their nourishment. At the same time it

distributes the natural grease over the whole coat, giving it an even

gloss. Long, clean strokes with the brush, exerting light pressure, and

following the grain of the coat serve both purposes. In order to give the

horse the highest gloss, a final rub down with a soft woollen cloth is most

effective. The body brush should not be too close-set, so that it can

penetrate the winter coat down to the skin. A rubber curry comb may be

used to help circulation. The mane and tail need to be carefully picked

out by hand each day, and, if necessary, washed. The dock also should be

well brushed out. Wash the eyes, muzzle, nostrils, sheath or udder, rectum

and vulva every day with a sponge. Frequently the hooves require daily

cleaning with a hoof pick; after work they should also be washed with a hard

brush and sponge, especially inside. Grease should only be applied, if at

all, to a perfectly clean hoof—and then use only the finest, colourless

grease on the inside and the coronet edge. During the warm season, massage

of the legs with a not-too-strong jet of water is quite beneficial.

Clipping varies a great deal from breed to breed, and

is very much subject to fashion. However, it must never be forgotten that

the mane and tail-hair have a special purpose in warding off insects, and that

cutting them may mean discomfort for the horse that could have been

avoided. Docking the tail is forbidden in Britain, Germany, and many other

countries. A horse which, because of inadequate care, cold stabling, or

some other reason has acquired an excessively heavy winter coat, should be

clipped. For after sweating into a lather at work, such a coat takes a

long time to dry out, and in some circumstances the horse may break out into a

sweat later, with a risk of catching cold. In the latter case it is better

to rug him up, first placing handfuls of straw on his back—when he is quite

dry, the straw may be removed and a fresh rug put on.

If an owner wishes to keep his horse in an efficient and

active condition then he must pay special attention to correct shoeing.

Although it is ideal when a horse can be used unshod, this is so unusual that

care must be taken to see that he has a new set of shoes every six to eight

weeks. Faulty conformation of the limbs of a foal and even of older

horses, as well as the possibility of injuries resulting therefrom, can be

removed, or at least minimised, by appropriate treatment, by prescribed standard

shoes, or by special orthopaedic shoes.

The axis of the toe of the correctly shaped hoof, with or

without shoes, and viewed from the front or side, forms a straight line with the

fetlock, running from the point of the fetlock joint to the toe. Unless

very necessary, the frog should not be trimmed back at all, and as much of it as

possible should come in contact with the ground, otherwise it may become

deformed and cause lameness. The completely flat shoe should be made to

fit the completely flat-trimmed hoof, not the reverse! Whether the shoe

should be burned on is still a moot point, for burning tends to dry out the

hoof. On the other hand, it gives a much simpler and more exact fit by

ensuring a very much flatter surface for the shoe. The outer edge of the

shoe must be slightly wider than the inner, at the same time protruding very

slightly beyond the sole of the foot. The heels of the shoe must end at a

line more or less perpendicular to the edge of the horse's heel, in order to

give the hoof adequate support and minimise strain on the tendons. The

heels of the shoe should not be too close together; the shoe itself must be

nailed to the crust of the wall of the hoof, great care being taken not to drive

the nails too close to the sensitive part of the foot.

To keep the horse in top physical condition, an essential

factor is his daily work. This must be so arranged that the horse

undertakes it each day with pleasure. The work may well tax the horse, but

only then will he spend the rest of the day free from boredom and the vices

arising therefrom. Ideally, the horse should be exercised twice a

day—once on the lunge and once saddled. The work should always end at

its height, when the horse is giving his best performance, and not when he

is already beginning to resist through fatigue. Always end with a lesson

the horse finds easy and therefore likes doing. By following this rule

closely, you will find that the horse's physical capabilities improve with each

outing. It is a good idea to add variety by riding cross-country, or

working over the cavaletti and on the lunge, for nothing makes a horse so dull

(and, of course, his rider too) as the stupefying regularity of the daily

grind. Regularity is only essential for grooming and feeding times in the

stables. The horse immediately responds to variety with a greater

willingness to work, and keenness to learn. An alert but quiet appearance

on the part of the trainer, and consistency in the treatment of the horse are

important. Generally the horse is a good pupil, yet too much should never

be asked of him.